D-Lib Magazine

May/June 2015

Volume 21, Number 5/6

Table of Contents

Linked Data URIs and Libraries: The Story So Far

Ioannis Papadakis, Konstantinos Kyprianos and Michalis Stefanidakis

Ionian University, Corfu, Greece

Corresponding Author: Konstantions Kyprianos, k.kyprianos@gmail.com

DOI: 10.1045/may2015-papadakis

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

The linked data movement is a relatively new trend on the web that, among other things, enables diverse data providers to publish their content in an interoperable, machine-understandable way. Libraries around the world appear to be embracing linked data technologies that render their content more accessible to both humans and computers. This paper focuses on linked data URIs that refer to authority data. We attempt to identify the specific MARC fields that are capable of hosting linked data information. Additionally, seven major national libraries are examined to determine to what degree they have adopted the fundamental linked data principles.

Keywords: Linked Data, LOD, MARC, Authorities, Libraries

1 Introduction

Traditionally, libraries provide access to collections via the employment of Online Public Access Catalogs (OPACs). The OPAC is a fundamental component of an Integrated Library System (ILS) since it facilitates access for the average user to information (both bibliographic and authority data) stored in MAchine-Readable Cataloging (MARC) format. At the beginning, the main purpose of an OPAC was to aid users in locating books on the shelves and/or linking books that share a common aspect (e.g. subject). Along these lines, library professionals throughout the years have collected valuable and high quality, authoritative information that can be utilized beyond the scope of the library OPAC.

This paper focuses on authority data and argues that such data should be made publicly available in a widely acceptable, machine-understandable format. Linked data technologies provide the means to render authority data within libraries part of the so-called Web of Data (WoD). The WoD refers to a vast amount of data on the web available in a standard, machine-readable format, which can be reached, linked and managed by adequate semantic web tools (Bizer, et al., 2008). To meet this goal, traditional MARC-based authority records should be enriched with linked data-specific information (i.e. linked open data (lod) URIs).

This work attempts to identify the MARC fields that are capable of hosting lod URIs. Seven major national libraries around the globe are examined with respect to their adoption of the fundamental linked data principles. Specific MARC fields that are employed by each library are examined in terms of their semantic ability to host locally- and remotely-defined lod URIs. The corresponding findings are analyzed and interesting results are drawn.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the next section, the procedure and technologies that libraries traditionally employ for the description, exchange and structuring of their authority data are presented. The corresponding MARC fields that can potentially accommodate locally- and remotely-defined lod URIs are stated in the following section. Then, the practices that national libraries currently employ to publish their data as linked data are shown. Next, a detailed description of the process that is needed for publishing the authority information of a library's catalog to a format suitable for the lod-cloud is presented. Finally, the last section concludes this paper.

2 Libraries and MARC

Structured interoperable data is not a new research agenda for libraries. Since the early 1960s, libraries have agreed upon the MARC standard for the arrangement of their data (Caplan, 2003). MARC suggests a data format that is employed to exchange, use and interpret bibliographic and authority information between libraries, thus enhancing interoperability between them. It employs a system of numbers, letters, and symbols to annotate information.

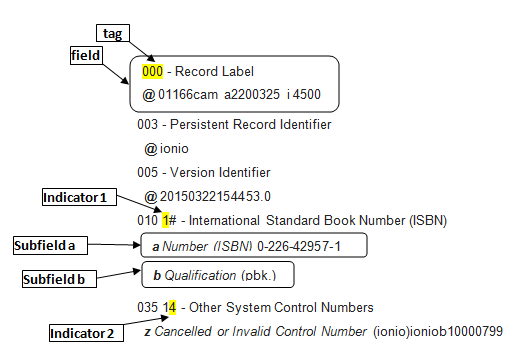

Every MARC record consists of fields, tags, indicators, subfields, subfield codes, and content designators (MARC Terms and Their Definitions). More specifically, each authority record is logically divided into fields. There are different fields to declare various descriptive information within the record. Each field is associated with a three digit number called tag. A tag identifies the kind of data that follows. Next, indicators provide more specific definitions to the corresponding fields. Indicators consist of two characters that follow each tag. None, one or both of them may be used. Each indicator is assigned a number from 0 to 9. The indicators are then followed by subfields. Subfields are marked by codes and delimiters.

Figure 1: A fictitious Marc Record

The fact that the MARC standard has been around for so many years has contributed to the creation of consistent and invaluable information within libraries. Such information is difficult to share and exchange with external entities. In an effort to make such data useful in the ever-evolving online environment, libraries across the world are currently experimenting with linked data technologies. In the following section, the MARC fields that can accommodate linked data information are presented.

3 MARC and Linked Data

The very nature of linked data intrigued the library community right from the beginning. Over the past few years, various libraries around the world have become active members of the lod-cloud (lod-cloud). This could be attributed to the fact that linked data is based on common web standards (i.e. HTTP, URI, etc.). Consequently, the resulting services are considered as easy to maintain and open to evolve (Baker, et al., 2011). Moreover, information exchange with patrons from different domains and areas is greatly facilitated (Malmsten, 2009).

According to Baker, et al. (2011), the first task a library has to accomplish in order to provide in-house data as linked data is to create persistent Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs), i.e. permalinks, for its resources. The WoD is based on the idea of unique identifiers and their interlinking (Heath & Bizer, 2011).

In this paper, locally-defined identifiers refer to identifiers that are created by the library that employs them, whereas remotely-defined identifiers refer to identifiers that are created by a different (i.e. remote) library than the one that employs them. For example, the control number (e.g. value of field 001) of an authority record is considered to be locally-defined, whereas other system control numbers (e.g. value of field 035) are considered to be remotely-defined.

In the following sections, an investigation is made to assess the potential of certain MARC21 (Library of Congress, 2013) and UNIMARC (Willer, 2009b) authority fields to host locally- and remotely-defined lod URIs. The decision to provide the MARC21 and UNIMARC fields that are compatible with linked data was made due to the fact that these two formats are the most common formats being used for the authority records' description and exchange between libraries. The fields that are included in the assessment are by definition capable of hosting identifiers.

3.1 MARC21, UNIMARC and Locally-defined lod URIs

As far as the creation of locally-defined lod URIs is concerned, libraries already employ unique identifiers (i.e. Control Numbers) for their records and the entities they describe in their daily routine. The information is kept in specific fields in MARC21 and UNIMARC. In the following paragraphs, the semantic compatibility of such fields with lod URIs is discussed. The discussion is based on the definition of each field as provided by the standards (i.e. MARC21 and UNIMARC) and their semantic interpretation as it is perceived by the authors. Table 1 presents the MARC fields that seem suitable candidates for hosting locally-defined lod URIs.

| Fields |

MARC21 |

UNIMARC |

| 001 |

Control Number |

Record Identifier |

| 003 |

— |

Persistent Record Identifier |

| 024 |

Other Standard Identifier |

— |

| 856 |

Electronic Location and Access |

Electronic Location and Access |

Table 1: MARC fields that may accommodate locally-defined lod URIs

Both MARC21 and UNIMARC employ field 001 to uniquely identify their authority records. Ideally, a next-generation, lod-ready library would have all of its records identified by a permalink that would be kept at field 001. In practice however, libraries use this non-repeatable field to keep system-generated, non-URI identifiers for their records, and any attempt to replace existing identifiers with lod URIs would most probably cause serious functionality issues to the whole system. Thus, each of the two predominant MARC standards provides a number of complementary fields for hosting unique identifiers that could potentially accommodate lod URIs.

More specifically, UNIMARC defines field 003 (Willer, 2009a) to accommodate a persistent identifier for the corresponding local authority record. Such a field is ideal for hosting lod URIs for authority records that are defined by the local agency. In a former edition, UNIMARC used to provide field 009 (UNIMARC and Cataloguing Rules (UNICAT)) to allow the cataloguer to fill-in an identifier other than the one that has been generated by the underlying system.

The MARC21 field 024 refers to a "Standard number or code associated with the entity named in the 1xx field which cannot be accommodated in another field (e.g., fields 020 (International Standard Book Number) and 022 (International Standard Serial Number)). The source of the standard number or code is identified in subfield $2 (Source of number or code)". If URIs are considered as 'codes', the definition above implies that field 024 may host a locally-defined lod URI as long as the MARC code referencing the local agency is stated in subfield $2.

At this point, it should be noted that UNIMARC and MARC21 follow a slightly different approach with respect to the entity that is referenced by the identifiers in the corresponding fields. More specifically, UNIMARC's definition of field 003 states that the identifier specified within this field should refer to an authority record, whereas MARC21's definition of field 024 states that the identifier specified within this field should refer to the entity described by the record. However, when it comes down to authorities, libraries create lod URIs that do not distinguish between the record and the corresponding entity.

Both standards provide field 856 that could presumably host locally-defined lod URIs. By definition, field 856 accommodates URLs capable of providing location and access to information about the corresponding authority record. This can also be verified by the fact that most of the provided indicators and subfields are related to Internet access protocols conveying information about the mechanics of URIs instead of the URIs per se. Thus, this field should not be employed for identification purposes. Instead, it should be employed to locate and access online information about the corresponding entity. From another point of view, a library that generates its own lod URIs for authority records and satisfies the second rule of linked data (i.e. "Use HTTP URIs so that people can look up those names"), could use both fields 003 (or, 024 in MARC21) for identification purposes and 856 for informational purposes.

The following section presents the MARC fields that are potentially capable of hosting remotely-defined lod URIs. Again, the corresponding findings are based on the standards and the semantics of each field, as perceived by the authors.

3.2 MARC21, UNIMARC and links to remotely-defined lod URIs

MARC in its current form may explicitly accommodate lod URIs referring to remotely-defined lod URIs. Table 2 presents the MARC fields that seem suitable candidates for hosting lod URIs originating from remote datasets.

| Fields |

MARC21 |

UNIMARC |

| 024 |

Other Standard Identifier |

— |

| 033 |

— |

Other System Persistent Record Identifier |

| 035 |

System Control Number |

Other System Control Numbers |

| 450 |

See From Tracing — Topical Term |

Variant Access Point — Topical Subject |

| 670 |

Source Data Found |

— |

| 750 |

Established Heading Linking Entry — Topical Term |

Authorized Access Point in Other Language and/or Script — Topical Subject |

| 810 |

— |

Source Data Found |

| 856 |

Electronic Location and Access |

Electronic Location and Access |

Table 2: MARC fields that may accommodate remotely-defined lod URIs

In the following paragraphs, a detailed discussion about the semantic compatibility of each of the above fields with remote lod URIs is presented.

As stated earlier in this paper, the MARC21 field 024 refers to a "Standard number or code associated with the entity named in the 1xx field which cannot be accommodated in another field (e.g., fields 020 (International Standard Book Number) and 022 (International Standard Serial Number)). The source of the standard number or code is identified in subfield $2 (Source of number or code)". According to the definition above, field 024 may host a remote lod URI as long as the source of such a URI is provided in subfield $2. The possible values of subfield $2 are specified in "Standard Identifier Source Codes", which states that this registry "... assigns a code to each database or publication that defines or contains the identifiers". It is apparent that the source codes that appear in the registry should refer to organizations that define or contain specific identifiers. However, this is not the case with source codes URI and URN. URI (and its derivative URN) does not provide identifiers. Instead, it is a syntax scheme that is employed from other systems that wish to define http-ready identifiers (viaf, doi, lccn etc.). It should also be mentioned that the above registry does not include a source code for the LoC authorities and vocabularies service. Thus, for the time being1, if a cataloguer decides to employ field 024 to refer to a lod URI from such a source (e.g. http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85000411), it is not possible to catalog the source of the URI in subfield $22.

UNIMARC field 033 (UNIMARC Authorities, 3rd edition. UPDATES 2012) was recently added to accommodate "the persistent identifier of records obtained from other sources. The persistent identifier is assigned by the agency, which creates, uses or issues the record. This is the persistent identifier for the bibliographic record, not for the entity itself ... The persistent identifier carried in a 033 field is the equivalent on the web of the system control number for the record in another database carried in a 035 field". The purpose of this field is to host URIs that can be looked-up by humans. Such URIs should correspond to authority records that have been created, used or issued by other agencies and accordingly imported 'as-is' from the local agency. Thus, field 033 is not suitable for hosting lod URIs referring to authority records that are not identical to the local authority record. Along these lines, this field is ideal for hosting lod URIs of authority records within aggregator catalogs (e.g. union catalogs).

Field 035 in MARC21 (and UNIMARC) contains a "control number for the record in a system other than the one whose control number is contained in field 001 (Control Number), 010 or 016. For interchange purposes, documentation of the structure and use of the system control number must be provided to exchange partners by the originating organization. Each valid system control number and any related canceled/invalid control number are contained in a separate 035 field", meaning that this field hosts identifiers for the specific authority record defined by other agencies. Possible values of field 035 should exist in field 001 of other systems. Thus, a lod URI could be added in field 035 of a local system, provided that the same URI exists in field 001 of a remote system.

Field 450 (and the similar 4xx fields) in UNIMARC and (MARC21) contains "a variant access point or a subject category in coded and/or textual form that is referred from". Field 450 is actually a variant (or, non-preferred term) of the authority hosted in fields 150 and 250 of MARC21 and UNIMARC respectively. This field hosts different, non-preferred verbalizations of the authority that do not have a separate identifier. Thus, field 450 should not host URIs of remote linked data resources.

Field 670 in MARC21 refers to a "citation for a consulted source in which information is found related in some manner to the entity represented by the authority record or related entities. May also include the information found in the source". Thus, field 670 provides a reference that has been explicitly created for the specific authority entity. Even if the subfields $a (i.e. $a: Source citation) and $u (i.e. $u: Uniform Resource Identifier) were (erroneously) employed to host the name of the referring source and the corresponding permalink respectively, there is no subfield available to define the kind of related information of the authority entity provided by the referring source. Thus, field 670 should not host URIs of remote linked data resources.

UNIMARC field 810 is the UNIMARC equivalent of field 670 in MARC21, which is defined as "a citation to a reference source when information about the heading was found. The first 810 field usually contains the citation for the bibliographic work for the cataloguing of which the heading has been established". Same as before, such a field is capable of hosting only generic references to the corresponding authority entity. Additionally, field 810 cannot accept URIs.

Field 750 in MARC21 (and the similar 7xx fields) is defined as a "topical term that is equivalent to the 150 topical term or 180 general subdivision heading field of the same record. It links headings within a system or from different thesauri or authority files". The type of relation between the authority records in fields 150 and 750 (i.e. local and remote) is addressed as "equivalent".

Additionally, field 750 includes subfield $0, defined as "the system control number of the related authority record, or a standard identifier such as an International Standard Name Identifier (ISNI). The control number or identifier is preceded by the appropriate MARC Organization code (for a related authority record) or the Standard Identifier source code (for a standard identifier scheme), enclosed in parentheses. See 'MARC Code List for Organizations' for a listing of organization codes and 'Standard Identifier Source Codes' for code systems for standard identifiers". Thus, subfield $0 could potentially host lod URIs provided that the corresponding standard identifier scheme has preceded its use.

As stated earlier in this paper, this definition does not allow referencing LCSH lod URIs, since the registry of Standard Identifier Source Codes does not include a code for the popular LoC authorities and vocabularies service. A reference to lcsh as a code for the Library of Congress Subject Headings should not exist in subfield $0, since such a system defines literals (i.e. subject headings), not identifiers. Field 750 also includes subfield $2, defined as "MARC code that identifies the thesaurus or authority file that is the source of the heading when the second indicator position contains value 7. Code from: Subject Heading and Term Source Codes for subfield $2 in fields 700-751". From the above definition, it is apparent that subfield $2 may refer to the agency that provides the corresponding authority label (not identifier). A reference to lcsh as a code for the Library of Congress Subject Headings should be provided in subfield $2.

To sum up, it seems that field 750 is capable of hosting lod URIs that refer to equivalent authority entities defined in remote systems.

Field 750 in UNIMARC is slightly different from its equivalent in MARC21. More specifically, it is defined as "a topical authorized access point or an authorized subject category access point that is in another language and/or script form of the 250 access point". Same as before, the relation between the authority records in 250 and 750 (i.e. local and remote) is addressed as "equivalent". Field 750 also contains a number of value-added subfields. More specifically, subfield $3 hosts the corresponding remote resource, subfield $2 hosts the MARC code of the agency that defines the remote resource and subfield $8 hosts the language of the corresponding resource. In contrast to its equivalent field in MARC21, UNIMARC field 750 is explicitly defined to host URIs in another language than the one that is used in the corresponding field 250. Thus, such a field is only suitable for hosting URIs of remote linked data resources in different languages.

Finally, as stated earlier in this paper, field 856 in MARC21 (and UNIMARC) contains "the information required to locate an electronic item. The field may be used in an authority record to provide supplementary information available electronically about the entity for which the record was created. The information identifies the electronic location containing the item or from which it is available. It also contains information to retrieve the item by the access method identified in the first indicator position. It can be used to generate notes relating to mode of access". Such fields refer to URLs that provide access and location to information about the authority record.

It is apparent that field 856 is designed for location access (i.e. not for identification purposes). However, the absence of a field capable of hosting remotely created identifiers referring to the same authority entity in UNIMARC, forced many libraries across the world to employ such a field to keep the corresponding VIAF identifier. This is not the case with MARC21, where VIAF identifiers may be hosted in field 024.

In the following section, the practices that national libraries around the globe actually follow to provide linked data information to their users are presented. The information was gathered by evaluating each library's website.

4 National Libraries, Authority Records, MARC and Linked Data

The libraries that participate in this survey are involved to a certain extent with the linked data movement. As a general remark, it is observed that locally-defined URIs are based on the values of specific MARC identifier fields and are accordingly stored in modern linked data services. More specifically, the creation of such URIs follows a certain pattern: Use a standard path as a prefix and use the value from the aforementioned MARC fields as a suffix. Such lod URIs are not stored in the traditional library catalog (i.e. OPACs). Remotely-defined lod URIs are stored both in the traditional library catalog and in modern linked data services. In the following sections, a detailed analysis of each library is presented.

4.1 Library of Congress (LoC)

The LoC maintains an authority file, namely "Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH)", containing authority records published in MARC21. Apart from field 001 that is used to uniquely describe every authority record, LoC also employs field 010 as the "Library of Congress Control Number (LCCN)". This is a unique number that accommodates identifiers from the LCCN permalink service. More specifically, LoC creates a permalink for each authority record by appending a specific prefix (i.e. "http://lccn.loc.gov/") to the corresponding authority record. For example, according to the aforementioned process, the resulting permalink for the authority record "Accounting" would be "http://lccn.loc.gov/sh85000411".

The LCCN permalink should not be thought of as the URI that uniquely identifies the corresponding authority record within the scope of the linked data movement. Instead, for this purpose, the LoC launched the id.loc.gov service to provide access through commonly found standards and vocabularies. This service provides resolvability to values and vocabularies by assigning URIs. Each URI consists of a given prefix (i.e. "http://id.loc.gov/"), a path describing the various datasets that are contained within the service (e.g. "authorities/subjects", authorities/names", etc.), a code adhering to each dataset (e.g. "sh" for subject headings, "n" for Name Authority File, etc.) and the corresponding 010 value. For example, the authority record "Accounting" is identified by the URI "http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85000411". Additionally, the linked data service of LCSH provides links to remote resources from other linked data providers such as RAMEAU, National Agricultural Library (NAL), Global Legal Information Network (GLIN), GND etc.

Finally, in 2011, LoC officially launched the Bibliographic Framework Initiative (Miller, et al., 2012). It aims to create a new environment for bibliographic description in libraries. The new model is called Bibliographic Framework (BIBFRAME) and it is expected to replace the MARC format and make libraries' collections available as a part of the semantic web. BIBFRAME also serves as a new model or ontology for describing bibliographic and authority data.

4.2 British Library (BL)

The British Library (BL) aligned British authority records (created for the British National Bibliography (BNB) from 1971-1987 and from 1995 onwards with LCSH British Library: Metadata services Standards: Subject Access in British Library Bibliographic Records. Current application of LCSH at the BL follows the principles, policies and guidelines given in the Library of Congress publication "Subject Cataloging Manual: Subject Headings3". The BL was formerly using the UKMARC as a standard for cataloguing authority records, which is no longer supported and has accordingly shifted to MARC21 (December 2008) (Hill, 2002).

The BL has recently launched the BNB as linked open data. It exploits the information of MARC21 field 150 to create locally-defined lod URIs. For example, the authority record "Accounting" would be "http://bnb.data.bl.uk/doc/concept/lcsh/Accounting". Such a lod URI is not kept within the library's catalog. The BL authority records provide links to remote resources deriving from the LCSH.

4.3 French National Library (BNF)

The French National Library (Bibliothéque nationale de France (BNF)) employs RAMEAU (Répertoire d'Autorité-Matière Encyclopédique et Alphabétique Unifié) to define its authority records. RAMEAU is based on the "Subject Cataloging Manual: Subject Headings" introduced by the LoC. The BNF uses UNIMARC as a standard for cataloguing authority records. Field 001 is employed to uniquely identify an authority record. Apart from field 001, BNF also employs field 009 as an authority record persistent identifier. For example, "Etablissements religieux" corresponds to "http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb11954011h".

Since July 2011, RAMEAU authority records are available as linked data. More specifically, the project data.bnf.fr aims to make the data of BNF (i.e. authors, works, etc.) (Wenz, et al., 2013) part of the semantic web. Data.bnf.fr allows: a) access to the resources of the BNF directly from a web page and b) access to external resources from other linked data providers, such as DBpedia, VIAF, etc. The unique URI of an authority record derives from the original record identifier number. More specifically, the resulting URIs contain the ARK identifier that is based on field 009. For example, the authority record "Etablissements religieux" corresponds to the lod URI: "http://data.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb11954011h".

4.4 German National Library (DNB)

The German National Library (Deutsche National Bibliothek (DNB)) employs MARC21 for its authority records. The DNB also provides the Gemeinsame Normdatei (GND), which is a national authority file for the organization of personal names, subject headings and corporate bodies from the catalog. It is mainly used for documentation in libraries and archives. The GND (Haffner, 2012) became operational in April 2012 and integrates the content of the following authority files which have been discontinued since then: a) Name Authority File (Personennamendatei (PND)), b) Corporate Bodies Authority File (Gemeinsame Körperschaftsdatei (GKD)), c) Subject Headings Authority File (Schlagwortnormdatei (SWD)) and d) Uniform Title File of the Deutsches Musikarchiv (Einheitssachtitel-Datei des Deutschen Musikarchivs; DMA-EST). The initial authority records identifiers have also been transferred into the new integrated catalog. For example, the authority record from the SWD "Management Accounting" has the unique identifier "4125415-6" both in GND and SWD (OGND). The URI that corresponds to the specific authority is "http://d-nb.info/gnd/4125415-6".

The DNB is planning to offer a linked data service which will permit the semantic web community to use the entire stock of their national bibliographic data, including all authority data (German National Library, 2013). Finally, the GND does not provide any associations to other linked data resources. It only provides associations to the STW thesaurus of economics.

4.5 National Library of Spain (BNE)

The National Library of Spain (Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE)) employs MARC21 for its authority records. Prior to MARC21, the library was using the IBERMARC. The transition was decided to facilitate the internationalization and standardization of the bibliographic records, the archive records and the authority control of the BNE. The unique identifier of each authority record is provided in field 001. Additionally, each authority record has field 670 that contains the authority record derived from RAMEAU, LCSH and TMA . For example, the authority record "Tecnología limpia" is the same as "Green technology" in LCSH, "Tecnologías blandas" in TMA Tesauro de Medio Ambientedel MOPU [Madrid]: Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo, 1990 and "Technologie douce" in RAMEAU. Additionally, field 024 hosts the URI from the corresponding LCSH.

The BNE initiated a joint project also involving the Ontology Engineering Group (OEG) to enrich the semantic web with bibliographic data from their catalogue. The project is called "datos.bne.es". The provided service contains information not only from the bibliographic records but also from the authorities records. Each lod URI follows a certain pattern. For example, the lod URI "http://datos.bne.es/tema/XX544630.html", which refers to the authority record "Tecnología limpia" is composed from field 001 (i.e. XX544630) as a suffix and the "http://datos.bne.es/tema/" as a prefix. The linked data service provides associations to LCSH.

4.6 National Library of Sweden (LIBRIS)

The National Library of Sweden (Kungliga Biblioteket (KB)) employs MARC21 for its authority records. The library consists of two main catalogues, which hold the majority of the KB collection, namely Regina and Swedish Media Database (SMDB). It also provides access to Sweden's national catalogue and a search tool with titles from university, research, higher education libraries and public libraries. The field that uniquely identifies a record in all catalogs is field 001. The library does not allow direct access to the authority file.

Since 2008, the Swedish Union Catalogue (i.e. LIBRIS) is available as linked data. It contains links to Wikipedia, DBPedia, LC authority files (names and subjects) and VIAF (Malmsten, 2009). Field 001 is employed to create the URIs of the linked data service. For example, the authority record "Modrar" identified by "154863" corresponds to the following URI: "http://libris.kb.se/auth/154863".

4.7 Hungarian National Library (NSL)

Finally, the Hungarian National Library (National Széchényi Library (NSL)) employs MARC21 for Hungarian authority records (Edelstein, et al., 2013). It uses field 001 to uniquely identify each record.

For the creation of the URIs the prefix: "http://nektar.oszk.hu/auth/" is employed together with the information from field 150. For example, the authority record "elbeszélés" corresponds to the URI: "http://nektar.oszk.hu/auth/elbeszélés". NSL provides associations to DBpedia and VIAF.

In the following section, a detailed description of the process that is needed for publishing the authority information of a library's catalog to a format suitable for the lod-cloud is presented.

5 Publishing Authority Files as Linked Data

This paper has so far investigated the potential of the traditional OPAC serving as a repository capable of keeping linked data URIs. This section focuses on the exploitation of such data for the creation of modern linked data services within libraries. Like any other data provider wishing to participate in the linked data movement, libraries need to comply with certain requirements. According to Berners-Lee (2006) the founder of the linked data movement, there is a set of four "rules" for publishing data on the Web in such a way that all published data becomes part of a single global data space:

- Use URIs as names for things.

A URI can represent any entity: a person, an object, an idea, etc. The URI is not the entity itself but a reference to it. The reference is always unequivocal, meaning that a URI always denotes one specific entity and only this entity.

- Use HTTP URIs so that people can look up those names.

A HTTP URI is a web address that can be accessed to retrieve information about the entity that is identified through that URI (Archer, et al., 2012). Employing standard web technologies (i.e. URIs) to identify the cell of linked data renders such data easily accessible not only from computer applications but also from humans. Moreover, the inherent ability of a URI to reference the organization responsible for the corresponding entity facilitates the overall management of URIs.

- When someone looks up a URI, provide useful information, using the standards (Resource Description Framework (RDF)) (Klyne & Carroll, 2004), SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL) (Prud'hommeaux & Seaborne, 2008)).

In the context of libraries, the simplest form of access to a specific URI is provided by a webpage with information from the catalog for the specific entity. Apart from that, such information should also be delivered in a standards-compliant format (i.e. RDF, SPARQL). This way, the provided information may be used by third-party computer applications.

- Include links to other URIs, so that more things may be discovered.

The true power of linked data lies in its ability to bring together entities from diverse systems. Along these lines, a library wishing to become a linked data provider should include URIs that refer to remote entities.

Compliance with the above design principles may be achieved through the adoption of certain tools and technologies (Hannemann & Kett, 2010). Such technologies should underpin the following concepts: a) URIs provide the means to identify the underlying data, b) RDF provides a conceptual scheme for modeling such data, c) for the serialization and the storage of data in a machine-readable format, triplestores are employed and finally, d) such data become available to interested parties through the employment of queries expressed in a dedicated query language, i.e. SPARQL (Isaac, et al., 2011).

Along these lines, major national libraries have developed dedicated linked data services on top of their OPACs. Such services are based on specialized datastores containing authority information that is modelled according to the aforementioned rules. The following sections describe the building blocks of such services.

5.1 Data Modeling

According to the third rule of linked data (see Section 5 above), data providers wishing to participate in the WoD should publish their data in RDF. The RDF data model is designed for use in the context of the web.

In RDF, a statement about a resource is modeled as a triple. A set of triples constitutes the RDF graph. A triple is comprised of a: a) subject, b) predicate and c) object. The subject is a URI (or a blank node, but this is a special case of a URI and it does not concern us in this paper); the object can be either a URI or a literal value such as a string, a number etc.; the predicate is always a URI and indicates what kind of relation exists between the subject and the object (Heath & Bizer, 2011). At this point, it should be mentioned that the RDF graph is just a conceptual model. Therefore, the RDF graph (i.e. a set of RDF triples) should be serialized in RDF syntax to be machine understandable. The most common RDF serialization formats are: a) RDF/XML (Beckett, 2004), b) RDFa (Herman, et al., 2013), c) Turtle (Beckett & Berners-Lee, 2008), d) N-Triples (Beckett, 2013) and e) RDF/JSON (Davis, et al., 2013).

When it comes down to expressing relations between authority entities (i.e. predicates), the library domain commonly employs the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS). SKOS is a RDF-based vocabulary for modelling authorities, such as Subject Headings, Thesauri descriptors or Taxonomies within the context of the Semantic Web (Isaac & Summers, 2009). It can be used on its own, or in combination with more formal languages such as the Web Ontology Language (OWL) (Dean & Schreiber, 2004; W3C OWL Working Group, 2012).

Table 3 presents the SKOS predicates that are semantically equivalent with the MARC fields (Summers, et al., 2008; Plassard, 2001) that are commonly found in authority files.

| MARC21 field code |

UNIMARC field code |

Field semantics |

SKOS predicates |

| 001 or 010 |

001 or 009 |

Control Number |

rdf:about |

| 150 |

250 |

Topical Term |

skos:preflLabel |

| 450 |

450 |

See From Tracing |

skos:altLabel |

| 550 $w (ind. 'g') (Only use this property when subfield $w has indicator 'g') |

550 $5 (ind. 'g') (Only use this property when subfield $5 has indicator 'g') |

See Also From Tracing |

skos:broader |

| 550 $w (ind. 'h') (Only use this property when subfield $w has indicator 'h') |

550 $5 (ind. 'h') (Only use this property when subfield $5 has indicator 'h') |

|

skos:narrower |

| 550 $w (w/o ind. 'g' or 'h') (Only use this property when subfield $w is presented without the indicators 'g' or 'h') |

550 $w (w/o ind. 'g' or 'h') (Only use this property when subfield $5 is presented without the indicators 'g' or 'h') |

|

skos:related |

Table 3: UNIMARC/MARC21 fields and their semantically equivalent SKOS predicates

For example, the following triple states that the URI "http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85000411" corresponds to the authority entity with the label "Accounting":

<http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85000411> skos:prefLabel "Accounting" .

In a similar manner, the following triple indicates that the authority entity with the label "Accounting" has a narrower meaning than the authority entity corresponding to the URI "http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85009477":

<http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85000411>

skos:narrower

<http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh85009477> .

As clarified in the following section, the RDF data that corresponds to the authority file within a library is essentially a triplestore consisting of triples similar to the above examples.

5.2 Data Access

Libraries keep their RDF data in lod-specific information systems commonly called triplestores. Triplestores are specialized database management systems for the storage and retrieval of RDF data (Rusher, 2010). Currently, many triplestores exist that serve different needs and demands (see Large Triple Stores). Some common triplestore engines are AllegroGraph, Virtuoso Universal Server, and Garlik 4store.

Triplestores facilitate access to their content through the employment of SPARQL endpoints. SPARQL is a query language that is able to retrieve and manipulate data available in RDF.

Triplestore content related to an authority entity can also be served directly when the corresponding URI of the authority is being accessed (e.g. by typing the URI to the Address bar of a Web browser). This access mechanism, often called "URI dereferencing", provides the subtle transition from the authority entity identified by the URI, to a page containing information about such an authority entity.

While there is little consensus today about what to serve as information related to an authority entity, the mechanism for accessing the information via the HTTP protocol is currently well established. The technology involved is advanced and all kinds of library applications may benefit from the availability of library information on the web as linked data. Accessing a lod URI involves the following steps:

- The URI of an authority entity is accessed as a normal web address. The requesting application can ask for machine-processable RDF data or a simple web page through a "content negotiation" access option.

- In most cases, a redirect ("303 See Other") is returned, providing a new location for the requested content. The new address refers to a document containing RDF or textual data about the authority entity.

- The requesting application (or a user's web browser) then accesses the newly provided location to retrieve the aforementioned data.

The previously mentioned redirection step (b) may seem superfluous; it is, however, the standardized way to access large linked data collections like the ones found in libraries. Conceptually, the URI of step (a) is an identifier of an entity (the requested authority entity), not an address of a web document. This fact is conveyed by the redirection reply. The redirection provides a second web address of a document containing information about the initial URI.

Apart from SPARQL endpoints and URI dereferencing, linked data-enabled libraries provide access to their data in bulk through RDF dumps. Table 4 presents the way national libraries publish their RDF data. This information was gathered by visiting the corresponding online library services.

| |

Library |

SPARQL endpoint |

Dump files |

Dereferencing |

| 1 |

BL (BNB) |

✔ |

|

|

| 2 |

BNF (RAMEAU) |

|

✔ |

✔ |

| 3 |

DNB (GND) (There is only an experimental SPARQL endpoint regarding the authority files of the DNB and can be accessed here.) |

|

✔ |

✔ |

| 4 |

BNE |

✔ |

|

|

| 5 |

KB (LIBRIS) |

✔ |

|

|

| 6 |

LOC (LCSH) |

|

✔ |

✔ |

| 7 |

NSL |

✔ |

|

|

Table 4: Libraries and services to the lod community

More details about the linked data services that each library offers are provided in datahub.io. This service provides a free, public domain registry of all the linked data providers on the web, along with information about the way they make their data available. Datahub.io works as an aggregator where patrons may register their data and make it available to the web community as linked data. It also brings together collections of specific domains.

5.3 Data Linking

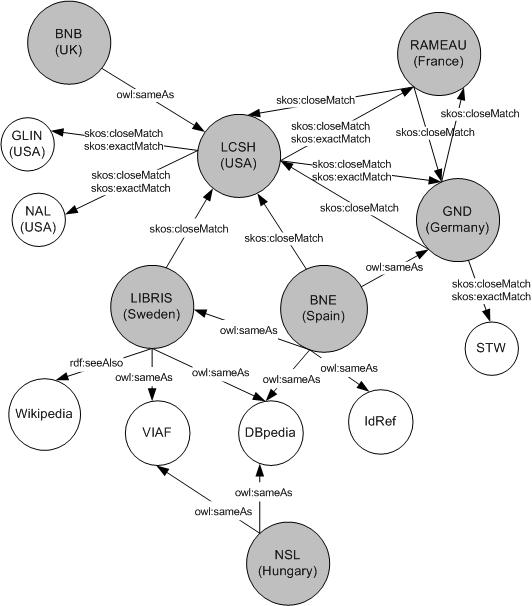

As discussed previously in this paper, the fourth rule of linked data states: "Include links to other URIs, so that more things may be discovered". In other words, linked data library services should contain triples consisting of URIs defined elsewhere. In Figure 1, the connectivity between major library linked data services is shown. National libraries appear as shadowed nodes, whereas transparent nodes correspond to other library-related linked data services. (Such information is inferred by visiting the corresponding online library services.) The arcs are labeled by the predicates that are employed to bring together resources from different data services.

Figure 2: Interlinking between libraries in the lod-cloud

Figure 2 shows that just a few predicates are employed for the interlinking of authority entities between libraries around the world. More specifically, 2 out of 7 libraries (i.e. BNB and NSL) employ the predicate "owl:sameAs" to interlink local authority entities with remote ones. 4 out of 7 libraries (i.e. LCSH, GND, RAMEAU and BNE) employ the SKOS vocabulary. RAMEAU and BNE employ the predicate "skos:closeMatch" whereas LCSH and GND employ the predicate "skos:exactMatch" when the local and the remote entities are exactly the same and the predicate "skos:closeMatch" when the local and the remote entities are loosely associated. It should also be mentioned that LIBRIS is the only linked data service that employs the "rdf:seeAlso" predicate when referring to entities exclusively deriving from Wikipedia, the predicate "skos:closeMatch" when referring to entities exclusively deriving from LCSH and the predicate "owl:sameAs" when referring to entities deriving from VIAF and DBpedia. Finally, most of the national libraries (4 out of 6) provide links to the LCSH service."

6 Conclusions

This paper considers the traditional OPAC within libraries and especially the authorities section as an invaluable source of information for library systems. The advent of the semantic web, and the linked data movement in particular, provide the opportunity to promote access to authority records in a standardized manner. For this purpose, authority records within OPACs need to be updated with linked data-specific information. The work reported here identified MARC fields that are capable of hosting such information. From a semantic point of view, the most suitable fields to host lod URIs of locally-defined authority records are fields 003 for UNIMARC and 024 for MARC21. When dealing with remotely-defined lod URIs that need to be referenced by the local OPAC, the most suitable field to host such information is field 7xx. However, in UNIMARC, that field type is not semantically compatible for hosting lod URIs that refer to remotely-defined entities, written in the same language as the local entity.

In practice, the national libraries included in this study (with the exception of the National Library of Spain) have not yet incorporated lod URIs to their OPACs. Instead, they use OPAC as their primary data store and accordingly build lod-related services that are based on the information derived from the underlying OPAC. It is the authors' belief that next generation ILS should adapt to the linked data principles and accordingly provide linked data services both to their users and the wider web community.

Notes

1 According to Discussion Paper No. 2010-DP02: Encoding URIs for controlled values in MARC Records: "Development and MARC Standards Office is developing a registry service for controlled lists and in so doing is establishing URIs both for the lists themselves and for each value on a list". Thus, things are expected to change in the future.

2 According to LoC, permalinks for the authority records are provided through lccn.loc.gov. However, such permalinks do not comply with the third rule of linked data. Thus, such information is practically inaccessible from other services.

3 Subject cataloging manual: subject headings. Prepared by the Cataloging Policy and Support Office, Library of Congress. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1996.

References

[1] Archer, P., Goedertier, S., & Loutas, N. (2012). Deliverable: D7.1.3 — Study on persistent URIs, with identification of best practices and recommendations on the topic for the MSs and the EC. European Union: Interoperability Solutions for European Public Administrations.

[2] Baker, T., Bermes, E., Coyle, K., Dunsire, G., Isaac, A., Murray, P., Panzer, M., Schneider, J., & Singer, R. (2011). Library Linked Data Incubator Group Final Report. W3C Incubator Group Report. World Wide Web Consortium.

[3] Beckett, D. (2004). RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised) — W3C Recommendation.

[4] Beckett, D., & Berners-Lee, T. (2008). Turtle —Terse RDF triple language.

[5] Beckett, D. (2013). N-Triples: A line-based syntax for an RDF graph — W3C Working Group Note.

[6] Berners-Lee, T. (2006). Linked Data — Design Issues.

[7] Bizer, C., Heath, T., Idehen, K., & Berners-Lee, T. (2008). Linked data on the Web (LDOW2008). In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on World Wide Web (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, 2008), 1265—1266.

[8] Caplan, P. (2003). Metadata fundamentals for all librarians. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

[9] Davis, I., Steiner, T., & Hors, A. J. (2013). RDF 1.1 JSON Alternate Serialization (RDF/JSON) — W3C Editor's Draft.

[10] Dean, M., & Schreiber, G. (2004). OWL Web Ontology Language Reference — W3C Recommendation.

[11] Edelstein, J., Galla, L., Li-Madeo, C., Marden, J., Rhonemus, A., & Whysel, N. (2013). Linked Open Data for Cultural Heritage: Evolution of an Information Technology.

[12] German National Library. (2013). The Linked Data Service of the German National Library: Modeling of bibliographic data. Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.

[13] Haffner, A. (2012). GND ontology. Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.

[14] Hannemann, J., & Kett, J. (2010). Linked data for libraries. In: Proceedings of the world library and information congress of the Int'l Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA).

[15] Heath, T., & Bizer, C. (2011). Linked Data: Evolving the Web into a Global Data Space. Synthesis Lectures on the Semantic Web: Theory and Technology, Morgan & Claypool, 1 (1), 1-136.

[16] Herman, I., Adida, B., Sporny, M., & Birbeck, M. (2013). Rdfa 1.1 primer Second edition: Rich Structured Data Markup for Web Documents — W3C Working Group Note.

[17] Hill, R. W. (2002). Changing the record: a concise guide to the differences between the UKMARC and MARC21 bibliographic formats. West Yorkshire: The British Library.

[18] Isaac, A., & Summers, E. (2009). SKOS Simple Knowledge Organization System Primer — W3C Working Group Note.

[19] Isaac, A., Waites, W., Young, J., & Zeng, M. (2011). Library Linked Data Incubator Group: Datasets, Value Vocabularies, and Metadata Element Sets — W3C Incubator Group Report.

[20] Klyne, G., & Carroll, J. J. (2004). Resource Description Framework (RDF): Concepts and Abstract Syntax — W3C Recommendation.

[21] Library of Congress (2013). MARC21 Format for Authority Data (Update no. 17).

[22] Malmsten, M. (2009). Exposing library data as linked data. In: IFLA satellite preconference sponsored by the Information Technology Section" Emerging trends in technology: Libraries between Web 2.0, the Semantic Web and search technology.

[23] Miller, E., Ogbuji, U., Mueller, V., & MacDougall, K. (2012). Bibliographic Framework as a Web of Data: Linked Data Model and Supporting Services. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

[24] Plassard, M. F. (2001). Authority Control in an International Environment: the UNIMARC Format for Authorities. In: 2nd workshop on Authority Control among Chinese, Korean and Japanese Languages held at National Institute of Informatics (NII) in cooperation with National Diet Library, 28-29 March 2001.

[25] Prud'hommeaux, E., & Seaborne, A. (2008). SPARQL Query Language for RDF — W3C Recommendation.

[26] Summers, E., Isaac, A., Redding, C., & Krech, D. (2008). LCSH, SKOS and Linked Data. In: Proceedings of the 8th International conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, 22-26 September 2008: DC-2008 Berlin, Dublin Core Metadata Initiative, 25-33.

[27] Vila-Suero, D., Villazón-Terrazas, B., & Gómez-Pérez, A. (2013). datos.bne.es: a Library Linked Data Dataset. Semantic Web. IOS Press, 4 (3), 307-313.

[28] W3C OWL Working Group (2012). OWL 2 Web Ontology Language: Document Overview (Second Edition) — W3C Recommendation.

[29] Wenz, R., Di Mascio, A., Michel, V. & Simon, A. (2013). Publishing bibliographic records on the web of data: opportunities for the BnF (French National Library). In: Extended Semantic Web Conference — ESWC 2013, Montpellier, France.

[30] Willer, M. (2009a). Third edition of UNIMARC Manual: Authorities Format: How does it implement concepts from the FRAD model and IME ICC Statement of International Cataloguing Principles. In: World Library and Information Congress: 75th IFLA General Conference and Council, 23-27 August 2009, Milan, Italy.

[31] Willer, M. (ed.) (2009b). UNIMARC Manual: Authorities Format. 3rd ed. Munchen: K. G. Saur.

About the Author

|

Ioannis Papadakis was born in Athens in 1975, and he received his Bachelor diploma in Computer Science from the University of Piraeus, in 1997. He obtained his Ph.D. in the field of Digital Libraries in the same Department in 2003 with the topic: "Digital Libraries: Architectures, Security and Information Retrieval". Since 2005, works at the Department of Archives, Library Science and Museology, at the School of Information Science and Informatics of Ionian University. During the past few years his scientific interests include the semantic web and linked data in particular, service-oriented digital libraries and the web in general.

|

|

Konstantinos Kyprianos was born in Athens. He received his bachelor diploma in Librarianship from ATEI of Athens in 2002. He attended his MSc in Computer Science at University of Piraeus. He is a Ph. D. candidate at the Department of Archives, Library Science and Museology, at the School of Information Science and Informatics of Ionian University with the topic "Information services based on controlled vocabularies and the semantic web". Currently, he is occupied as a System Librarian at the Library of University of Piraeus. His research interests include the semantic web, linked data and digital libraries in general.

|

|

Michalis Stefanidakis holds a Diploma of Computer Engineering and Informatics and a Ph.D. in Design and Performance Evaluation of Distributed Memory Parallel Computer Architectures from the University of Patras. Currently he is occupied as an Assistant Professor at Ionian University, Department of Informatics. His research interests include the Semantic Web and Linked Data, Pervasive Computing and High-Performance Distributed Processing.

|

|