|

D-Lib Magazine

May/June 2013

Volume 19, Number 5/6

Table of Contents

A Model for Providing Web 2.0 Services to Cultural Heritage Institutions: The IMLS DCC Flickr Feasibility Study

Jacob Jett, Megan Senseney, Carole L. Palmer

University of Illinois

{jjett, mfsense2, clpalmer}@illinois.edu

doi:10.1045/may2013-jett

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

The Flickr Feasibility Study, which was launched by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Digital Collections and Content (DCC) project in 2009 to determine how aggregators might provide intermediary services for cultural heritage institutions wishing to engage in Web 2.0 initiatives, shed light on both needs and models for aggregation services. This article provides an overview of the study's findings, including the efficiencies that aggregation services such as the DCC can afford cultural heritage institutions when they act as intermediaries to facilitate Web 2.0 participation. Also discussed are the outcomes of the study's conversations with Yahoo, Inc. representatives regarding aggregators as members of the Commons on Flickr and the complimentary cultural heritage spaces that aggregation services can help their member institutions to create outside of the Commons. Finally, the ample rewards in long-tail community engagement and user-generated metadata that cultural heritage institutions can reap when they expose their collections to Web 2.0 communities, are highlighted.

I. Introduction

In 2009 the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Digital Collections and Content (DCC) project launched the Flickr Feasibility Study (FFS), a pilot to investigate extending the DCC aggregator role to support our data providers' participation in Web 2.0 communities. The data providers are cultural heritage institutions maintaining one or more digital repositories whose collections have been aggregated by the IMLS DCC. During the course of the pilot project we experienced firsthand the considerable barriers to moving cultural heritage content into a Web 2.0 space. In addition to examining these barriers, we discovered that cultural heritage institutions have a need to participate in Web 2.0 Community Spaces beyond the boundaries established by current cultural heritage community spaces such as The Commons on Flickr. This paper explores selected outcomes and findings from the FFS and recommends a framework through which aggregators can facilitate engagement with Web 2.0 Communities by cultural heritage institutions.

II. Context

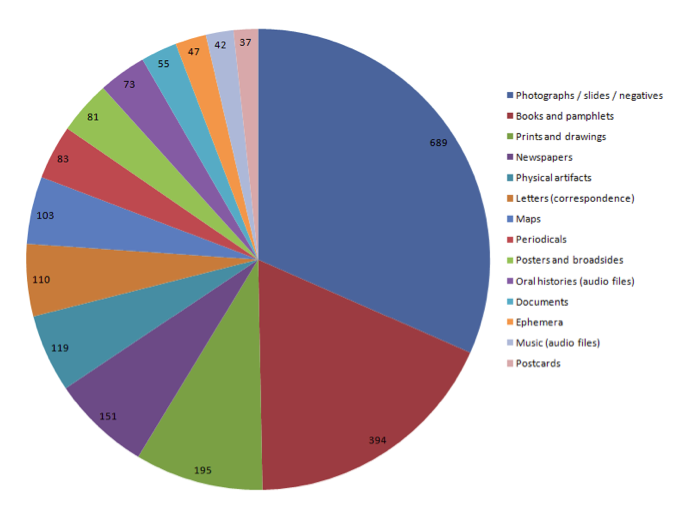

Funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services since 2002, the DCC currently provides a single point of access to nearly 1,500 collections with over one million items from 1,100 libraries, museums, archives, and other cultural heritage institutions. The aggregation includes collections from 48 states, the Library of Congress, and two unincorporated U.S. territories. The content of the aggregated collections is highly heterogeneous, including a variety of textual, visual, and audiovisual resources (see Figure 1). The aggregation service integrates collection-level and item-level metadata to facilitate searching and browsing while retaining the institutional identities and collection contexts that are vital to how users explore and interact with cultural heritage resources.

Figure 1: Top 15 item types in the IMLS DCC aggregation

Figure 1: Top 15 item types in the IMLS DCC aggregation

Of the collections within the aggregation, photograph collections, especially those consisting of snapshots, like the Charles W. Cushman Collection, or those with significant perspectives on local history, such as the Wing Luke Asian Museum collection, were inspected for potential inclusion in the FFS. Using these general criteria, collections from five data providers were selected for the pilot. The data providers ranged in size from small public libraries to large universities. Similarly, the collections selected ranged from very small (e.g., the Springfield Aviation Company Archives Collection) to very large (the aforementioned Charles W. Cushman Collection at the Indiana University Archives). Through our early interactions with the digital librarians and other stakeholders at the institutions, it became clear that the proposed Flickr service would play a welcome role in helping cultural heritage institutions expose their digital collections to a wider public audience through Web 2.0 services (Jett et al., 2010).

In previous publications we have provided details on the content selection process and workflows of the FFS (Jett et al., 2012; Jett et al., 2010). Here we provide an overview of select FFS findings, including the economies of scale aggregators afford when acting as intermediaries for cultural heritage institutions, the benefits of being able to share cultural heritage content outside the constraints of The Commons on Flickr, and the manner in which connecting with users through their tags, comments and community curatorial activities on Flickr Groups helps cultural heritage institutions identify and engage with communities that have developed around niche thematic interests relevant to the content of their collections. The FFS also reinforced the findings of previous Flickr studies (Springer et al., 2008; Zarro & Allen, 2010), which demonstrated the value that cultural heritage institutions can gain from user-generated metadata about their photos.

III. Proposal to Join The Commons using an Aggregation Membership Model

The initial plan for FFS was to contribute to Flickr as part of The Commons, developed in 2008 by Flickr and the Library of Congress to expose the hidden photographic collections of libraries, museums, and archives (Springer et al., 2008). The mission of increasing exposure to cultural heritage materials is consistent with how the DCC was initially conceived in 2002 and aligns with the project's goal to increase the national scope of content and diversity of institutions represented beginning in 2007. The two primary objectives of The Commons are "to increase access" to the photographic collections of cultural heritage institutions and to encourage the general public "to contribute information and knowledge" about the photographs in the form of notes, tags, and comments. To apply to join The Commons, a cultural heritage institution must submit a registration form and assert that there are "no known copyright restrictions" on the images uploaded to The Commons, sign a Flickr Service Agreement, and promise to remain active participants by regularly adding new images and interacting with the Flickr community.

In the fall of 2009, when the DCC registered to join The Commons, Flickr had developed a backlog of requests. A few months later, Flickr posted a statement on their registration page that they would not be accepting new registrations or requests to join The Commons through 2010 (Tennant, 2010). By April 2010, our negotiations to join The Commons began in earnest. The initial conversations suggested that the aggregation model offered by the DCC not only benefited data providers but might also offer a partial solution to The Commons' registration backlog by providing a single point of membership for multiple cultural heritage institutions. The other major point of discussion, the Flickr Commons service agreement, required lengthy periods of institutional review by IMLS and the University of Illinois, completed in mid-2011.

First, the project team worked to revise their cooperative agreement between IMLS and the University of Illinois, designating the University Board of Trustees as the signatory to the Flickr Service Agreement. The service agreement was then assessed by the University of Illinois' Office of Sponsored Projects & Research Administration (OSPRA). One key issue for the University concerning the terms of service in the agreement was the "Choice of Law; Forum" clause, which mandated that all signatories agreed to abide by the laws of the state of California (C. Palmer, personal communication, August 17, 2011). At the time that negotiations with Flickr began, the terms of this clause were found to be undesirable since the University of Illinois (a public institution of the State of Illinois) was only willing to sign agreements that were governed by Illinois' laws. By the summer of 2011 OSPRA consented to sign the agreement and indicated that they would also like the institutions participating in the FFS to be signatories (M. Murray, personal communication, July 30, 2011).

During this time, Flickr experienced considerable staff turnover (Pepitone, 2010), and we lost the representatives who had been involved in the initial negotiation process. After establishing new contacts in August 2011, the first discussion revealed less enthusiasm for aggregator participation in The Commons, and shortly thereafter the project team was notified that the DCC did not fit the current model for membership in The Commons. The new representatives expressed concerns that an aggregation model would break the direct connection between Flickr users and cultural heritage institutions that The Commons hoped to foster. Another concern related to how institutional authority would be established and whether there was potential confusion regarding rights to content. Finally, on a purely infrastructural level, Yahoo (and, by extension, Flickr) has no method of creating "group" or "nested" accounts, which they indicated would be necessary for an aggregator managing collections for multiple institutions (F. Miller & C. Weems, personal communication, November 1, 2011).

The DCC was not the only aggregator to face this problem. Both Minnesota Reflections and the Western Waters Digital Library, state and regional aggregators respectively, sought to join The Commons on behalf of their member institutions. In a 2008 project report, Minnesota detailed their extensive preparations for joining The Commons and anticipated that they would finalize their membership by 2009 (MINITEX Library Information Network, 2008). As of December 2012, neither aggregator has joined. While the DCC team has not pursued further engagement with the Yahoo representatives, they did suggest they would be open to further discussion at a later point if the DCC presented a more detailed business case for developing an alternative membership model for aggregators.

IV. Benefits of the Aggregation Membership Model Outside The Commons

During protracted efforts to join The Commons, the project team decided to launch the FFS using a Flickr Pro account and a Creative Commons licensing option, an approach that the project team had observed among other cultural heritage institutions, such as the U.S. National Archives, that had also been unable to get into the Commons during the period when Flickr was not taking new registration requests. In October 2009, the project team uploaded an initial batch of 317 photos from the Charles Overstreet Collection to the IMLS DCC Flickr Photostream. By the end of May 2011, the pilot study had grown to include 4,471 photographs from 5 institutions comprising 8 collections arranged into 24 "sets". While interacting with stakeholders from five pilot institutions and reviewing their content for inclusion in the study, the project team made two key observations: 1) an aggregation model supports institutions, large and small, that may not have the resources necessary to sustain an active, long-term commitment to Web 2.0 initiatives, and 2) the policies and digital content maintained by many cultural heritage institutions may not conform to The Commons' requirements for participation, thus reducing the possibility of fully exposing otherwise eligible digital collections from libraries, museums, and archives.

For an individual institution, contributing to Flickr requires either personnel time devoted to manually uploading photographs and transcribing metadata or the technical skill to exploit Flickr APIs, or one of several derived client toolkits, for example the Sammu tool developed by the Balboa Park Online Collaborative. Participation also requires an ongoing commitment of time and effort. According to the Flickr Commons registration page, new images must be added "on a regular basis", and institutions must agree to "read and respond to feedback given by the Flickr community" and "love it [their photostream] like it's a newborn lamb". Our interactions with FFS data providers suggest that many institutions are likely to lack the human resources, expertise, or infrastructure needed for these kinds of digital projects. Smaller institutions may not be able to afford the necessary technical staff, and larger institutions may not have sufficient personnel to prioritize moving into Web 2.0 initiatives.

An aggregator like the DCC, however, specializes in representing heterogeneous collections from various types of institutions and is well positioned to achieve efficiencies of scale by coordinating participation across multiple institutions. In addition to developing workflows for uploading content, FFS developed a metadata scheme that retains the identity of institutions and collections and interacted with Flickr users to integrate DCC images into their communities. The DCC team also recorded examples of Flickr users leaving comments that clarified or corrected metadata associated with DCC photographs. These efforts effectively consolidated the costs of both human and technical resources and greatly reduced the burden of participation for individual institutions. The FFS data providers only needed to commit to content selection and metadata review.

While the overall benefits of an aggregation model for cultural heritage institutions have been outlined above, there are also specific advantages to implementing this model outside The Commons. During recruitment for the FFS, we encountered data providers who were eager to share their content but were uncomfortable doing so without some form of restriction, which suggests that cultural heritage institutions need Web 2.0 community spaces that allow them to claim copyrights and specify reuse policies for their cultural heritage resources. Members of The Commons, however, are required to assert a "no known copyright restrictions" rights statement, which is intended to allow for the release of unrestricted photographs without formally asserting that the images are in the public domain (Springer et al., 2008). Notably for the FFS, it would not have been possible to provide access to what has proven to be the most popular collection in the DCC's stream within the confines of this rights statement, and the suite of Creative Commons licensing options offered the flexibility needed by our data providers for the digital objects they are permitted to share. Each institution participating in the FFS was amenable to using existing Creative Commons licensing terms, and the majority of participating institutions selected the relatively unobtrusive CC BY 2.0 license. This license allows for image reuse when formally attributed "in the manner specified by the author or licensor" with each new use. (Creative Commons, n.d.)

During negotiations with representatives from Flickr, we also learned that The Commons currently requires participating institutions to upload high resolution images, measuring at least 1024px on one side [T. Kirchner & C. Stoddard, personal communication, April 2010]. For a variety of reasons, many of our data providers either did not have or were not willing to share their digitized content at high resolution. For example, early digitization initiatives that prioritized access over preservation may have chosen to digitize content at fairly low resolution for public access online while focusing preservation efforts on the physical object being digitized (Watson & Graham, 1998). In such cases, scanning at a lower resolution was a reasonable, cost-effective decision, especially when considering the expense of disk space storage and network bandwidth, which could often be prohibitive, and the likelihood that lower display resolutions would have obviated high resolution images. If high resolution images are produced, it is common practice to incorporate them into a sustainability model in which the institution charges a fee for access to high quality images suitable for reproduction and distribution while making low-resolution copies freely accessible online. This approach balances the goal of free public access with the financial means for the institution to support the costs of stewardship of the originals (Allen, 1998).

V. Exposing Collections and Engaging Communities

Pushing content out to services like Flickr furthers the goal of the DCC aggregation to provide an integrative alternative to the silo effect created by access limited to institutional websites and repositories (Zorich, Waibel, & Erway, 2008). With exposure to Flickr's 51 million registered users, the eight collections showcased in the DCC's photostream receive an average of 22,829 views per month, dwarfing the usage statistics for the more than 1,400 collections aggregated by the DCC. Web 2.0 capabilities also expand opportunities for institutions and the public to actively use unique digital library and museum materials.

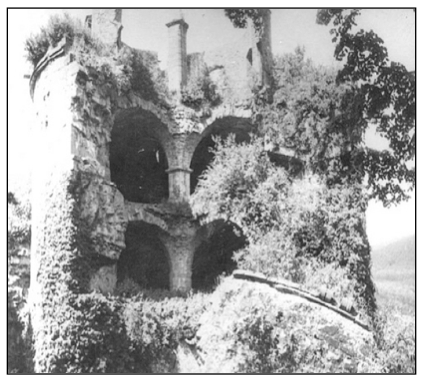

The DCC's photostream is being used in the four ways that Zarro and Allen (2010) determined users contribute to cultural heritage content on Flickr: expanding upon information provided, linking images to other resources, providing corrections to information provided, and curating images into new collections. The first three are valuable for institutions aiming to incorporate user-generated data into their library systems and have received quite a bit of attention by the digital library community (Library of Congress, 2008; Springer et al., 2008; Zarro & Allen, 2010). Of these, the most noteworthy interactions for the FSS have been instances in which users provide corrections or clarifications to the information provided about images in the FFS photostream. One such example is a photograph, Figure 2 below, from the Flora Public Library's Charles Overstreet Collection, which depicts a badly damaged castle tower. The description for the photograph speculates that the castle had been damaged during World War I, but a Flickr user clarifies in the comments that the Heidelberg castle in the photograph is frequently referred to as the "Powder Tower" and that it had been destroyed during the War of Palatinate Secession (also known as the Nine Years' War, circa 1688-1697).

Figure 2: "Heidelburg, Germany" courtesy of the Flora Public Library's Charles Overstreet Collection

Figure 2: "Heidelburg, Germany" courtesy of the Flora Public Library's Charles Overstreet Collection

Community curation of data providers' photographs into communal collections, however, is the most frequent form of interaction that Flickr users have with the images used in the FFS. This form of community curation is an interesting trend that has not yet been widely examined. Terras (2011) described these integrated collections as having "novel, detailed, and niche content with a very specific scope" with curation activities being initiated in one of two ways: by proactively participating—joining the group and adding photos to the "group photopool", or reactively participating—receiving a request for photos from a group's administrator to add to the "group photopool". The "group photopool" is the shared, community curated collection of pictures that each Flickr Group maintains.

The DCC participates in a total of 82 groups on Flickr. Thirty-seven of these are cases of reactive participation in groups which have requested DCC images for reuse. The groups range from very broad collections, such as B&W (Black & White), a group that collects black and white photographs, or WWII, which collects World War II photographs, to very narrow topics, such as Classic Motor Yachts, Colliery & Mine Photos, Old Family Pictures With Cars In Them, and Ticket Booth. Participation, especially with the niche, long-tail groups, has been instrumental in defining prominent themes within the existing collections, such as clowns, shipwrecks, and antique vehicles. As emergent subject strengths are identified both within and across collections, new opportunities become apparent to data providers for both collection development and collaboration to build new cross-institutional special collections (Palmer, Zavalina, & Fenlon, 2010).

VI. Discussion and Conclusions

The benefits of sharing cultural heritage collections through Web 2.0 services such as Flickr have already been well documented (Affleck, 2007; Burgess, 2007; Zarro & Allen, 2010). The FFS went further, investigating how cultural heritage institutions can realistically contribute to and derive value from a social online content sharing environment, which Terras (2011) describes as inherently community driven. Flickr contributors are active members of that community, sharing a web space that helps define both user expectations and the mutual experience of users and institutions interacting with one another. Through such community interactions, users contribute to an institution's understanding of its resources and to other users' understandings of those resources. These contributions can come via the addition of small details, such as tags or notes, or through more substantial annotations such as user comments. Additionally, Flickr affords participating institutions non-traditional methods of engaging with large masses of users through communal collection curatorial activities in the form of Flickr Groups. The FFS demonstrated that an aggregation service can efficiently integrate cultural heritage digital materials into the Web 2.0 environment, interact with Flickr's vibrant online community on behalf participating cultural heritage institutions, and observe community interactions with an eye toward augmenting the value of an institution's photographic collections.

A number of important lessons in developing the FFS have also contributed to the successful pilot, especially how to implement systematic metadata processing while prioritizing the need to retain the local institutional and collection contexts when representing content in the larger Web 2.0 landscape. By exploring the potential role of aggregators as intermediary service providers for cultural heritage institutions, the project team also observed discrepancies between the expressed needs of our stakeholders and the requirements of The Commons, one of the best-known and most popular initiatives for providing a single point of access to a variety of cultural heritage materials. Though The Commons' intellectual property policies and technical requirements may prove insurmountable for many cultural heritage institutions, we discovered that providing access to cultural heritage materials through a standard Flickr photostream is an equally viable method of providing broader access to collections and engaging with Flickr's vibrant and knowledgeable user community. The DCC team worked closely with different types of institutions to design an approach that not only filled a gap in human and technical resources for smaller institutions but also helped larger institutions participate more quickly and efficiently. It is now evident that, due to the diversity of cultural heritage institutions and their collections, services geared toward sharing cultural heritage content must maintain flexible policies, as institutional decisions ranging from intellectual property restrictions to shareable image resolutions are tightly linked to local services and constituencies.

A series of factors make it difficult for institutions to share their content through The Commons on Flickr, beginning with the registration bottleneck and then complicated by the technical demands and potential mismatch of the rights statement. While aggregators do not fit within the institutional membership model of The Commons, we found that they are uniquely positioned to lower the barriers to participation faced by cultural heritage institutions. Outside The Commons, an aggregator can leverage their technical capabilities and service operations in ways that are responsive to data provider needs, allowing institutions to, for example, determine the resolution of images to be shared through Flickr and assert optimal intellectual property rights through the Creative Commons licensing framework.

References

[1] Affleck, J. (2007). Memory capsules: discursive interpretation of cultural heritage through digital media. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Hong Kong.

[2] Allen, N. S. (1998). Institutionalizing digitization. Collection Management, 22(3-4), 217-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J105v22n03_23

[3] Burgess, J. (2007). Vernacular creativity and new media. (Doctoral dissertation). Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology.

[4] Creative Commons. "Creative Commons — Attribution 2.0 Generic." Creative Commons, n.d.

[5] Jett, J., Palmer, C. L., Fenlon, K., & Chao, Z. (2010), Extending the reach of our collective cultural heritage: The IMLS DCC Flickr Feasibility Study. Proc. Am. Soc. Info. Sci. Tech., 47: 1-2.

[6] Jett, J., Senseney, M., & Palmer, C.L. (2012), Enhancing Cultural Heritage Collections by Supporting and Analyzing Participation in Flickr. Proc. Am. Soc. Info. Sci. Tech., 49: 1-4.

[7] Library of Congress. (2008). On the record: Report of the Library of Congress Working Group on the Future of Bibliographic Control.

[8] MINITEX Library Information Network. (2008). Minnesota LSTA FFY2008 final report. Minneapolis, MN: Ewing.

[9] Palmer, Carole L., Zavalina, Oksana, & Fenlon, Katrina. (2010). Beyond size and search: Building contextual mass in aggregations for scholarly use. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology Annual Meeting, October 24-27, 2010, Pittsburgh, PA.

[10] Pepitone, J. (2010, December 14). Yahoo layoffs: 600 jobs cut in long-rumored move. CNN Money.

[11] Springer, M., Dulabahn, B., Michel, P., Natanson, B., Reser, D., Woodward, D., & Zinkham, H. (2008). For the Common Good: The Library of Congress Flickr Pilot Project.

[12] Tennant, R. (2010, January 25). Tragedy of the (Flickr) Commons? The Digital Shift. [Web log post]. January 25, 2010.

[13] Terras, M. (2011). The Digital Wunderkammer: Flickr as a Platform for Amateur Cultural and Heritage Content. Library Trends, 59(4), 686-706. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lib.2011.0022

[14] Watson, A., & Graham, P. (1998). CSS Alabama digital collection: a special collections digitization project. American Archivist, 61(1), 124-134.

[15] Zarro, M.A. & Allen, R.B. (2010). User-Contributed Descriptive Metadata for Libraries and Cultural Institutions. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 6273, 46-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-15464-5_7

[16] Zorich, D., Waibel, G. & Erway, R. (2008). Beyond the silos of the LAMs: Collaboration among libraries, archives and museums. Report produced by OCLC Programs and Research.

About the Authors

|

Jacob Jett completed his Master of Science in Library and Information Science in 2007 and a Certificate of Advanced Studies in Digital Libraries in 2010 from the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He currently works as a Project Coordinator for the Center for Informatics Research in Science & Scholarship. His research interests include data curation, information organization, data modeling, and metadata practices.

|

|

Megan Senseney completed a Master of Science in Library and Information Science in 2008 from the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where she currently works as Project Coordinator for Research Services. Her research interests include library history, special collections, digital humanities, and data curation.

|

|

Carole L. Palmer is a Professor in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science and Director of the Center for Informatics Research in Science and Scholarship (CIRSS) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her research is aimed at advancing large-scale digital research collections and the curation of research data for interdisciplinary inquiry and innovation. She has served as Principal Investigator of the IMLS Digital Collections and Content project since 2007, a foundational part of the CIRSS research and education initiatives on collection building and data curation in the sciences and humanities.

|

|