|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |

D-Lib Magazine

November/December 2014

Volume 20, Number 11/12

A Keyquery-Based Classification System for CORE

Michael Völske, Tim Gollub, Matthias Hagen and Benno Stein

Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, Weimar, Germany

{michael.voelske, tim.gollub, matthias.hagen, benno.stein}@uni-weimar.de

doi:10.1045/november2014-voelske

Abstract

We apply keyquery-based taxonomy composition to compute a classification system for the CORE dataset, a shared crawl of about 850,000 scientific papers. Keyquery-based taxonomy composition can be understood as a two-phase hierarchical document clustering technique that utilizes search queries as cluster labels: In a first phase, the document collection is indexed by a reference search engine, and the documents are tagged with the search queries they are relevant—for their so-called keyqueries. In a second phase, a hierarchical clustering is formed from the keyqueries within an iterative process. We use the explicit topic model ESA as document retrieval model in order to index the CORE dataset in the reference search engine. Under the ESA retrieval model, documents are represented as vectors of similarities to Wikipedia articles; a methodology proven to be advantageous for text categorization tasks. Our paper presents the generated taxonomy and reports on quantitative properties such as document coverage and processing requirements.

Keywords: Dynamic Taxonomy Composition, Keyquery, Classification Systems, Reverted Index, Big Data Problem

1. Introduction and Related Work

Classification systems form the heart of any library information system. For library maintainers, classification systems provide an effective means to overview a library's inventory. For library users, classification systems facilitate the structured exploration of large document sets. The manual development and maintenance of a classification system is a complex and time consuming task, raising the question whether and at which quality this task can be automated. In this paper we demonstrate how to compute a taxonomic classification system for a digital library (or a subset thereof) using keyquery-based taxonomy composition, a document clustering technique recently proposed by Gollub, et al. [7]. Specifically, we present a classification system that we computed for CORE (a crawl of 850,000 scientific papers), which serves as a shared dataset for the Third International Workshop on Mining Scientific Publications, and which currently lacks subject-oriented classification.

In the following, we briefly introduce the concepts behind keyquery-based taxonomy composition and give pointers to related work where appropriate. Section 2 describes the technical details of our data processing pipeline, and explains various design decisions. Section 3 presents an excerpt of the computed CORE classification system along with informative statistics.

A taxonomic classification system, like any taxonomy, is an arrangement of terms in a tree-like structure, where parent-child relationships indicate that the parent term semantically subsumes the child term. A taxonomy can hence be defined as a pair (T,≤), where T is a terminology (the set of terms), and ≤ is a reflexive and transitive binary relation over T called subsumption (the parent-child relationships) [10]. The idea of keyquery-based taxonomy composition is to treat the inverted index µ : V → 2D of a reference search engine as a model from which a taxonomy can be inferred (we use the notation 2X to denote the powerset of X). For the terminology T, a subset of all queries that can be formulated using µ's vocabulary V is taken. The subsumption ≤ is inferred from µ's postlists, each holding a subset of the indexed document collection D. Specifically, a term t1 ∈ T is assumed to subsume a term t2 ∈ T, t2 ≤ t1 if the result list Dt2 is a subset of Dt1, Dt2 ⊂ Dt1. Further, it is assumed that the reference search engine captures semantic subsumptions only roughly, and that a tolerance level must be introduced that allows to infer a subsumption relationship already if the subset relationship holds only to a certain extent. To this end, keyquery-based taxonomy composition introduces a two-phase document clustering algorithm that determines, for a given parent term, a collection of child terms which are (1) largely subsumed by the parent term, and (2) together maximize the recall with respect to the parent term's post-list. Applied to each term in T, the clustering algorithm eventually finds all subsumptions induced by the reference search engine.

In the light of the classification of document clustering algorithms by Carpineto, et al. [4], this two-phase clustering algorithm can be termed a description-centered clustering algorithm. Clustering algorithms of this type follow the intuition that meaningful cluster descriptions are essential for a clustering from a user perspective, and hence, their formation should be the driving force of the cluster analysis. Within keyquery-based taxonomy composition, the notion of meaningful is defined as follows: A term is a meaningful description of a cluster if a reference search engine queried with that term will retrieve the cluster's documents. This definition implies that the potential clusters of a document are given by the queries for which it is retrieved. These queries are called the keyqueries of a document, and they are determined and stored in a keyquery acquisition phase preceding the actual cluster formation process.

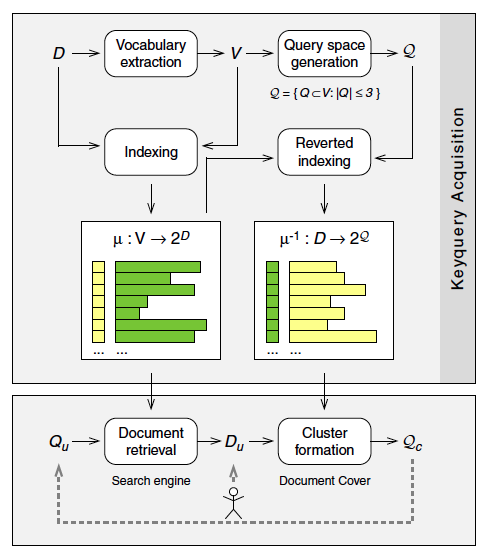

This two-phase approach is illustrated in Figure 1. The upper part of the figure shows the process of keyquery acquisition, whereas the lower part illustrates the cluster formation.

Figure 1: Conceptual overview for composing classification systems for arbitrary library subsets. The upper part of the figure shows the offline keyquery acquisition and assignment component, which both determines all keyqueries for the library documents and stores them in the reverted index. The lower part of the figure shows the online cluster formation component, which iteratively composes sublevels Qc for a user provided library subset Du. The composition of sublevels is controlled by the user, who selects a query Qu from the current taxonomy level Qc.

Keyquery Acquisition. To determine the keyqueries for a document collection D, a reference search engine that indexes the documents has to be set up (left column of Figure 1). The reference search engine employs the inverted index µ in order to retrieve the relevant documents Du for a query Qu. For the documents D of a digital library, a search engine may probably exist and can be directly applied for our purposes. For the CORE dataset, we set up a new reference search engine that employs explicit semantic analysis, ESA, as retrieval model [6]; see Section 2.1 for details.

From the inverted index µ, the reverted index µ-1 can be computed, which lists every document of D in its keyset and stores the document's keyqueries as postlists [9] (right column of Figure 1). To compute the keyqueries for the documents in D, the vocabulary V of the inverted index is used to formulate search queries that consist of terms from V. Together, these queries form the terminology for our taxonomy: the query space Q. During the reverted indexing process each query in Q is submitted to the search engine, and the returned documents are stored in the respective postlists of the reverted index. Note that this procedure can be seen as a general framework for automated tagging, and actually, depending on the specific reference search engine used, existing approaches to this task may be approximated under this framework [12, 5].

Cluster Formation. The cluster formation process is illustrated in the lower part of Figure 1; it is initiated by providing a document set Du. For our task of composing a classification for the CORE dataset, Du corresponds to the entire CORE collection D. However, a powerful feature of keyquery-based taxonomy composition is that it can dynamically compose tailored classification systems for arbitrary subsets of D. Especially, Du could be the search results for a query submitted to the reference search engine, giving rise to an interesting application in exploratory search settings [13].

To form a clustering for the given documents Du, a set of k queries Qc is sought whose search results cover Du with high recall, and which are subsumed by Du with high precision. For each query Q, its recall with respect to Du is defined as |DQ ∩ Du|/|Du|, whereas its precision is defined as |DQ ∩ Du|/|DQ|. The variable k controls the maximum number of clusters in the clustering and is set to twelve in our application as suggested in the original paper. To find the best clustering for Du, the reverted index could be exploited in different ways. First, the whole set Du can be submitted to the reverted index, which in turn responds with a list of all keyqueries Q that appear in any of the postlists for Du, ranked according to their frequency of appearance (= |DQ ∩ Du|). This approach is employed by the greedy set cover algorithm DocumentCover, which we use to compose the CORE classification system. DocumentCover is described in Section 2.2. Alternatively, the reverted index could be queried one document at a time to construct a keyquery-document matrix for Du. This matrix could then form the basis of an agglomerative cluster formation process [2, 3]. Since, independent from the cluster formation approach, a clustering is defined to be a set of queries, it is ensured that only clusterings Qc with meaningful cluster labels are formed. This implication can be phrased also as a query constraint within constraint clustering terminology [1]: Two documents cannot link if they do not share a common keyquery.

Given the clustering Qc for the initial Du, a hierarchical clustering (i.e., a classification system) can be achieved by submitting each keyquery of Qc to the reference search engine, which in turn triggers the generation of clusterings for the next sublevel. For the CORE dataset, we repeat this iterative process until the hierarchy is three levels deep. The resulting clustering is used as the classification system for CORE in the next section.

2. Application to CORE

The CORE dataset provides a convenient real-world testbed for keyquery-based taxonomy composition. Out of the 850,000 total articles in the data dump, we limit our analysis to articles where English full-text is available. To further improve the quality of the dataset, we try to filter out articles with parsing errors by discarding those whose average word length is more than two standard deviations from the mean of 6.5 characters. These filtering steps result in a set of about 450,000 articles, which form the foundation for the experiment presented below.

2.1 Keyquery Acquisition

The major design decision that has to be made in the keyquery acquisition phase is the selection of a retrieval model for the reference search engine. Our retrieval model of choice for CORE is the explicit topic model ESA [6], because it possesses, in comparison to bag-of-words or latent topic models, outstanding properties for our task.

Domain Knowledge. ESA represents documents via their similarity to a set of Wikipedia articles. Since we know that the CORE dataset consists of academic papers from various disciplines, we can incorporate this domain knowledge by choosing the Wikipedia articles for ESA accordingly. We select all articles referenced on Wikipedia's "List of Academic Disciplines" page, and we further enrich the set by articles whose titles appear in more than 100 CORE papers. In total, we extract 4,830 articles from the English Wikipedia dump for February 2, 2014.

Query Representation. The titles of the selected articles also form the vocabulary V, i.e. the query space Q is set equal to the topic space of ESA, which has an interesting effect when it comes to answering queries. Typically, to answer queries under a topic model, queries are treated as (tiny) documents in the vocabulary space. To identify relevant documents, the query is transferred from the vocabulary space to the topic space first, and its similarity to documents in the topic space is then used as relevance metric. The explicit topics of ESA allow us to pursue an alternative relevance assessment strategy which aligns well with the idea of queries as higher level concepts: Queries are treated as documents that already reside in the topic space, and relevance scores can be computed directly. This works since all query terms have—by vocabulary design—a well-defined representation in the topic space of ESA.

Implicit Relevance. As a final argument for the use of ESA, unlike bag-of-words models like TfIdf, ESA is capable of finding relevant documents that do not contain the query terms explicitly. Especially for general terms—like those one would expect on the first level of a taxonomy—this is an important property, since they are known to appear rarely explicitly in relevant documents [10]. With ESA, to be relevant for a query term, a document only needs to be similar to the respective Wikipedia article. To compute the similarity between documents and Wikipedia articles, we represent each document and each Wikipedia article under a BM25 retrieval model, and compute the dot product for each document-article pair. Given 450,000 CORE documents and 4,830 Wikipedia articles, this yields an 450,000-by-4,830 similarity matrix, where each of the column vectors contains the similarity distribution for one Wikipedia topic. Since these document-topic similarity distributions tend to be long-tailed, with many documents achieving a low similarity score, we apply the sparsification criterion from [8], setting similarities which are not significantly above a computed expected similarity score to zero. For every CORE document, we consider the set of Wikipedia articles with non-zero similarity scores to be its keyqueries. We store the mapping µ from each keyquery to documents in an inverted index. The mapping µ-1from each document to its keyqueries is stored in a reverted index for efficient access during cluster formation.

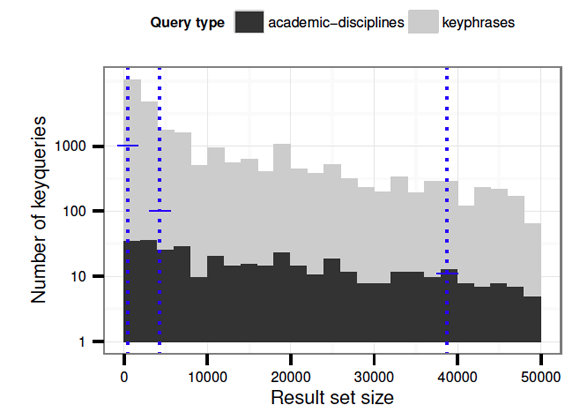

Figure 2 shows the frequency distribution of keyqueries in the reverted index. Given a fan-out parameter k = 12 and a target depth of three for the taxonomy, keyquery-based taxonomy composition proceeds in a level-wise manner, first splitting the entire collection into 12 top-level classes, then incrementally subdividing subclasses up to the leaf level. For the chosen taxonomy parameters, the overlaid vertical bars in Figure 2 show the optimal result set sizes for the leaf, middle and top level, from left to right. The horizontal cross bars superimposed on each level show the minimum number of queries needed at a given depth. Note that the "Academic Disciplines" topics alone suffice to fill out the top level of the taxonomy, whereas the lower levels require additional articles selected from document keyphrases. As noted, the full set of Wikipedia topics forms the query space Q for the cluster-formation process.

Figure 2: Distribution of query result set sizes in the reverted index for the CORE dataset. The overlaid vertical lines show the optimal result set sizes for the generated taxonomy of depth 3; horizontal crossbars show the minimum number of queries needed at a given level.

2.2 Cluster Formation

The cluster formation step can be stated as an iterative optimization problem. Given a document set Du to subdivide, the objective is to find the k-subset of the query space Q that maximizes recall with respect to Du, subject to the constraint that the maximum fan-out of k is never exceeded.

We employ Greedy Document Cover to approximate the solution to this optimization problem [7]. The algorithm subdivides a single document set Du into k subclasses using keyqueries from the reverted index; it is applied iteratively to the resulting subclasses until the leaf level of the taxonomy is reached. Next to Du and k, the algorithm receives as input the target class size t, which is computed as |Du|/k, and a slack parameter m = 50% which allows the result set size of the keyqueries to deviate by some margin.

In order to subdivide a document set Du, the algorithm retrieves from the reverted index the set of candidate queries Qu that return documents from Du. In order to select keyqueries on each taxonomy level that are subsumptions of their parents, we restrict the set of candidate queries to those with a precision greater than 0.8 with respect to Du (as in [11]). In up to k iterations, the algorithm selects the candidate query that maximizes recall—with respect to those documents in Du that have not yet been assigned to a subclass—as a child term in the taxonomy. The algorithm terminates when the maximum fan-out of k is reached, or when no further candidate queries meeting the constraints are available. Any remaining documents in Du are assigned to a "Miscellaneous" class.

We implement Greedy Document Cover as a series of MapReduce jobs, and store the query space Q and the document sets in the distributed file system of our Hadoop cluster. Each Map job filters its input queries with respect to the constraints given by t and m, and emits the results with appropriate keys. The intersection of the documents retrieved by each candidate query with the not-yet retrieved subset of Du is processed by a corresponding Reduce operation. The latter then computes each candidate query's precision and recall, and a subsequent MapReduce stage selects the candidate query to use in the current taxonomy branch. For managing the data flow between the different job stages, we employ the Scalding distributed processing framework.

Generating the classification system for the entire CORE dataset on our 40-node cluster takes about 48 hours of wall-clock time. Taxonomy generation for an entire digital library taking a long time is not a major issue—the classification system can be updated periodically by a nightly batch job. However, processing time is problematic in a live retrieval setting, where the document set returned by a user's query is to be subdivided in real-time. As outlined in [7], we propose an on-demand generation of taxonomy levels as a possible solution: compute only those branches of the classification system that the user explores while surveying her search results.

3. Results & Conclusions

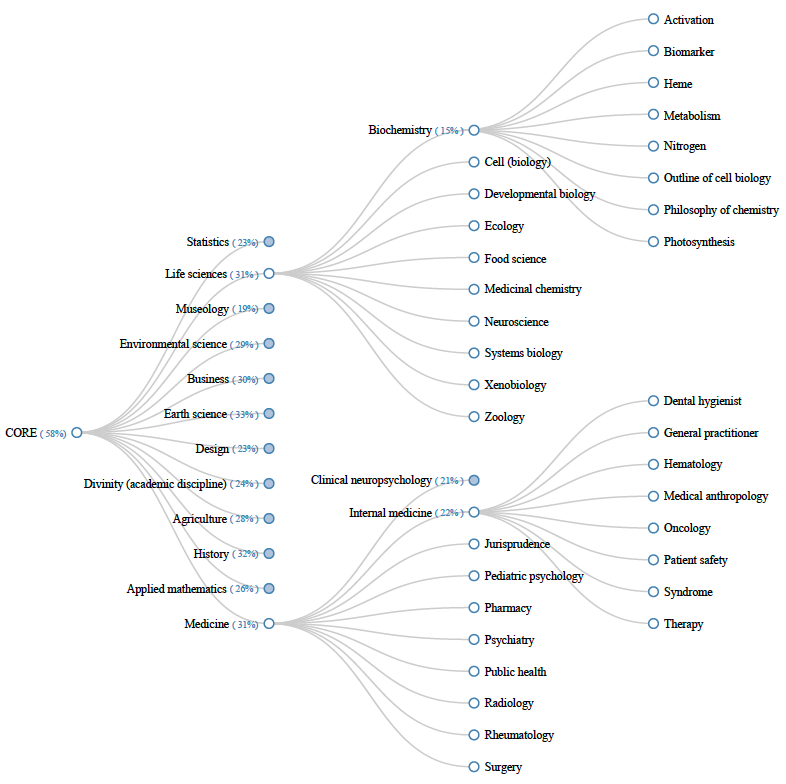

Figure 3 shows an excerpt of our classification system for the CORE dataset. The top level classes, subdivide the collection with respect to the academic disciplines given as input with an average pairwise overlap of 12%. Through the use of tailored Wikipedia articles, the top level of our taxonomy meets the common expectations of a library classification system. The subclasses for two of the top-level and mid-level categories are shown in the middle and on the right of the figure, respectively. For the second and third level classes, we observe a clear semantic connection to the respective parent classes. However, our approach does not produce an obvious semantic connection between sibling classes; it's not possible to guess the tenth sibling from studying the first nine. The percentage of documents covered by a given taxonomy subtree is shown in brackets next to each non-leaf label. Our keyquery-based classification system covers a total of 58% of the CORE subset considered in our experiment; the average coverage across all non-leaf taxonomy classes is 26%, indicating that despite the use of ESA as retrieval model, finding a classification at a high level of abstraction is a major challenge.

Figure 3: Excerpt of a partial keyquery-based taxonomy generated for the CORE dataset. For each non-leaf class, the percentage of documents covered by its subtree is shown in brackets next to the class label.

In conclusion, while our results so far are very promising, our taxonomy composition approach could benefit from a more in-depth evaluation. A comprehensive study of digital library users performing real-world retrieval tasks would help assess the usefulness of dynamically-generated classification systems. The semantic structure of the Wikipedia-based index collection makes for somewhat salient classes in the classification system, but our approach does not guarantee complementary sibling classes. Concept relationships mined from knowledge bases like Probase may help alleviate this weakness by further constraining the set of permissible candidate queries in a given Document Cover iteration.

References

[1] S. Basu, I. Davidson, and K. Wagstaff. Constrained Clustering: Advances in Algorithms, Theory, and Applications. Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2008. ISBN-13: 978-1450410649

[2] F. Beil, M. Ester, and X. Xu. Frequent term-based text clustering. In SIGKDD, 2002. ACM. http://doi.org/10.1145/775047.775110

[3] F. Bonchi, C. Castillo, D. Donato, and A. Gionis. Topical query decomposition. In SIGKDD, 2008. ACM. http://doi.org/10.1145/1401890.1401902

[4] C. Carpineto, S. Osinński, G. Romano, and D. Weiss. A Survey of Web Clustering Engines. Computing Surveys, 2009. ACM. http://doi.org/10.1145/1541880.1541884

[5] N. Erbs, I. Gurevych, and M. Rittberger. Bringing order to digital libraries: From keyphrase extraction to index term assignment. D-Lib Magazine, 2013. http://doi.org/10.1045/september2013-erbs

[6] E. Gabrilovich and S. Markovitch. Computing semantic relatedness using wikipedia-based explicit semantic analysis. In IJCAI, 2007. Morgan Kaufmann.

[7] T. Gollub, M. Hagen, M. Völske, and B. Stein. Dynamic Taxonomy Composition via Keyqueries. In DL (JCDL & TPDL), 2014. ACM/IEEE.

[8] T. Gollub and B. Stein. Unsupervised Sparsification of Similarity Graphs. In IFCS & GFKL, 2010. Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10745-0_7

[9] J. Pickens, M. Cooper, and G. Golovchinsky. Reverted indexing for feedback and expansion. In CIKM, 2010. ACM. http://doi.org/10.1145/1871437.1871571

[10] G. Sacco and Y. Tzitzikas. Dynamic Taxonomies and Faceted Search: Theory, Practice, and Experience. In Information Retrieval Series, 2009. Springer. ISBN-13: 978-3642023590

[11] M. Sanderson and B. Croft. Deriving concept hierarchies from text. In SIGIR, 1999. ACM. http://doi.org/10.1145/312624.312679

[12] S. Tuarob, L. C. Pouchard, and C. L. Giles. Automatic tag recommendation for metadata annotation using probabilistic topic modeling. In JCDL, 2013. ACM. http://doi.org/10.1145/2467696.2467706

[13] R. White and R. Roth. Exploratory Search: Beyond the Query-Response Paradigm. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services, 2009. Morgan & Claypool. http://doi.org/10.2200/S00174ED1V01Y200901ICR003

About the Authors

|

Michael Völske completed his M.Sc. in Computer Science and Media at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar in 2013 and joined the Web Technology and Information Systems research group the same year. His research interests include clustering, text reuse, and web search. |

|

Tim Gollub studied Media Systems at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. In 2008, he received his Diploma degree and joined the research group Web Technology and Information Systems at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar as a research assistant. Tim's current research focuses on the cross-sections of information retrieval, data mining, and web technologies. |

|

Matthias Hagen is Junior Professor at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar and head of the junior research group "Big Data Analytics." His current research interests include information retrieval and web search (e.g., query formulation, query segmentation, log analysis, search sessions and missions), Big Data, crowd sourcing, and text reuse. |

|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |