|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |

D-Lib Magazine

September/October 2011

Volume 17, Number 9/10

Digitization Practices for Translations: Lessons Learned from the Our Americas Archive Partnership Project

Lorena Gauthereau-Bryson, Robert Estep, Monica Rivero

Rice University

Point of contact for this article: Monica Rivero, monica.p.rivero@rice.edu

doi:10.1045/september2011-rivero

Abstract

The "Our Americas Archive Partnership" (OAAP) is a collaborative effort between scholars, librarians, and information scientists, and provides an integrated approach to discovering, accessing and using scholarly works that exist in multiple digital repositories. The archive is comprised of electronic texts and images originally written in or about the Americas from 1492 to approximately 1920. Its goal is to represent the full range and complexity of a multilingual "Americas" and to foster new research examining American literatures and histories from a hemispheric perspective. This paper discusses the complexities involved in digitizing multilingual historical documents, including practices for creating "born-digital" translations and unique metadata to best describe these rare, primary documents.

Introduction

The Our Americas Archive Partnership (OAAP) is a collaboration between Rice University, the University of Maryland's Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH), and Instituto Mora — Fondo Antiguo Biblioteca Ernesto de la Torre Villar (Mexico) to develop a common interface for American Studies scholars to discover digital resources that support their research and teaching. The work has included the development of a federated search interface to support resource discovery across the partners' sites, digitization of unique archival materials, and efforts to address the complexity of multilingual digital documents. This project was funded by an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) National Leadership grant.[1] The collections collectively span a period of 500 years and focus on the cultural transformation period that saw the making of modern and colonial cultures in the Americas from 1492 to the 1920s[2]. Many documents are original government publications such as constitutions, decrees, or presidential and congressional messages, as well as broadsides and pamphlets serving as public statements regarding the political and social events of the time, and firsthand accounts in the form of diaries and journals. In total there are 1,416 items in the OAAP and non-English texts comprise almost 50 percent of the contents. One of the key challenges for the archive was the digitization of these non-English texts along with a selection of related translations. A total of 94 translations (over 1,300 pages) were completed during this project. More than 30 librarians, archivists, scholars and information scientists participated in documenting these digital resources using qualified Dublin Core metadata and Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) P5 mark-up encoding for texts. During the project, novel digitization practices for translations were developed and refined; these approaches are the focus of this paper, along with the "lessons learned" throughout the process.

Translations: A scholarly perspective

The main objective of OAAP is to "facilitate current critical work in inter-Americas and hemispheric studies, spurring new possibilities and directions for comparativist approaches to the Americas."[3] The archive incorporates many Spanish-language primary documents, not previously available from current on-line platforms, along with their translations into English. The translations seek to enforce the trans-hemispheric, multilingual goal of the OAAP itself. Though the archive includes full-text versions for all original-language documents, a different approach was taken for translations. The OAAP includes both full translations of some diaries and books, as well as excerpts of longer documents. The selection of excerpt translations was made with a view towards expanding the range of accessible documents, so as to provide a wider sample of what is available. In this way the full breadth of the collection could be acknowledged. Later submissions may also include an assortment of excerpts, as a way to present content in other languages.

Translation of historical documents requires much more than knowledge of multiple languages; it also requires research into specialized terminology. Furthermore, idiomatic phrases must be translated into modern day equivalents, rather than directly translated, to maintain the author's original meaning. In addition, finer epistemological resonances must be negotiated to maintain the tone of the source document.

An added value of OAAP digital translations is the inclusion of the translator's annotations to explain historic, untranslatable or archaic terms, as well as references to events, locations, persons, etc., that may not be as well known today as they were when the documents were originally written. Translations include allusions to foreign canonical or historical figures, such as "the Prudent King" (Philip II of Spain), or "the Monk of Yuste" (Charles I of Spain); explanations of colonial legal terminology and military ranks; and a deciphering of a variety of abbreviations which authors commonly employed to conserve ink and paper[4]. These specialized notes provide a general context for modern readers and for those unacquainted with a document's related history.

Online treatment of "Born-Digital" translations

The online treatment of "born-digital" translations (that is, translations that do not exist in print format, but were created for digital publication) raises both academic and logistical questions in terms of presentation, description and item-level representation.

An initial survey of existing online collections that appeared to contain "born-digital" translations was conducted at the beginning of the project[5]. No universal treatment of "born-digital" translations was found to exist. Some collections elected to present translated text, and the original text, side by side. Some supplied what appeared to be only translated text, but were vague about where the source document existed, who created the translation or in what language the original text might have been. Surprisingly, the most common characteristic found was a lack of information about the translations and methodology used to create them.

Translations are not surrogates for the original documents; rather they are closely tied to, and best used in conjunction with, the original text for scholarly interpretation and research. From a digital archive perspective, however, treating the translation as a separate item allows for better usability as the document can be assigned unique descriptive metadata and discovered independently from the source document (for example by language). This treatment also allows for translation documents to be discovered by browsing through the site's map and timeline tools and assigning user tags. Therefore, the OAAP treats translations as stand-alone documents in the digital archive. In order to facilitate the needs of users to compare translations to the original text, the archive also includes page images of each original document, as well as a cross reference link to the source document's electronic version and a detailed metadata description about both the translation and the source document.

Text encoding

All texts in the OAAP collections were marked-up using XML (Extensible Mark-up Language) following the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) guidelines[6] to enhance full-text searches, increase their online usability and provide a mechanism for capturing historical or informational annotations at relevant points within the document itself.

The enhancement of search functions occurs behind the scenes, where the OAAP system converts XML files into plain text and then processes expanded abbreviations, regularized words (a search for the modern spelling of "Texas" would yield documents containing the archaic spelling: "Tejas"), annotations, and any data that may have been included within the XML tags themselves. This becomes very important when dealing with special characters, a common feature of historical archives of non-English texts, so that searches containing phrases with and without diacritics produce the same results. For example, the OAAP search platform treats "México" and "Mexico" (with and without an accent mark) as the same word so that the search results produce all occurrences of either word (with and without the e-acute character). This system design required a conscious decision in the programming of the OAAP search engine. Without this normalization of diacritics in the search function, it would be very difficult for a researcher to find all relevant content, because historical documents most likely do not contain modern accent markings, or may vary with language standards of the day, or even with a single writer at various points within the same document. Due to the inconsistency of such markings, normalization of diacritics is a way to support successful searches. Though diacritics are normalized for searching purposes, the actual documents are marked-up faithfully, or as close to the original author's markings as possible, for display purposes, and page images of the original documents are included for visual comparison.

Another benefit of TEI mark-up is that it provides a semantic structuring of the text. These logical divisions can be used to customize the presentation of the online text, including the creation of a hyperlinked table of contents. Since the OAAP archive includes many lengthy books and legal documents, many of which span over 300 pages, clickable tables of contents make navigation of this type of material less cumbersome. Users have the option of jumping to a specific section by clicking on the division titles or numbers, as opposed to scrolling through the entire document. Other online usability features include the display of mouse-over comments, hyperlinks to footnotes and endnotes and embedded full metadata records including provenance and other source information for archival materials.

Text mark-up also allows for insertion of historical or contextual annotations directly within the relevant passages. This capability is especially helpful in many of the Spanish manuscripts that contain archaic terminology or historical references. While an advanced Spanish-speaking scholar may be familiar with such terminology, students or researchers who may not be as experienced with archival materials may have difficulty interpreting them. In fact, many historical terms do not have accurate translations, and literal translations often erase their historical context. One example is the term "congregas," which appears several times in the collection of handwritten documents, "Papeles sobre la reducción del Seno Mexicano y Sierra Gorda"[7] ("Documents regarding the religious conversion in the Seno Mexicano and Sierra Gorda"). A literal translation would be "congregations" or "assemblies." Yet, the term "congregas" in colonial New Spain referred to a subjugating system in which the Spaniards would compel the Indians into villages (called "congregas") and then use these Indians for slave labor. Since a translation would erase the Spanish colonial meaning, the translation actually maintains the Spanish term (in italics, to signify that it is a foreign word) and includes a definition in the translator's footnote. With access to the context of such historical terms preserved in the original language, the reader can then conduct further research on the subject by searching for the term in its original language.

Other forms of archaic terminology include antiquated abbreviations and spellings. Another useful application of TEI encoding is to provide a reader with expanded versions or regularized spellings of these sorts of terms, such as: "Bejar" (Bexar County) or "Mejico" (Mexico).

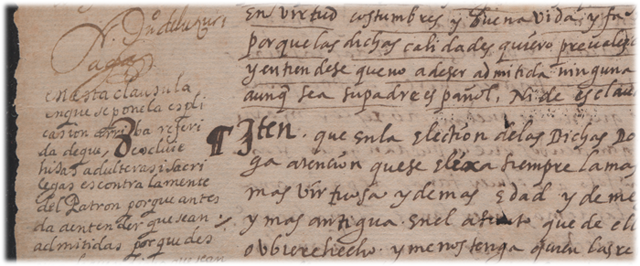

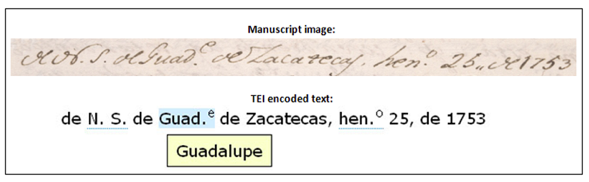

Figure 1: Application of TEI encoding used to help decipher archaic abbreviations

The marked-up document presents the original spelling as inline text denoted by a dotted underline. When moused over, the text is highlighted in blue and a display of the expanded text is shown in a yellow pop-up box. In the above example the name "Guadalupe" was often abbreviated as "Guad.e"; N.S. (Nuestra Señora) and henº (enero) are other acronyms with supplied expanded text.

While text mark-up enriches the documents by helping to preserve the text in its original form, converting it for full text searching and providing semantic structure for customizable presentation, the work of transforming page images to TEI encoded text is a labor intensive process. It requires a considerable time investment in terms of training in TEI encoding, strong quality control and review measures, supporting technologies such as custom stylesheets (XSLT) for transforming XML and system infrastructure to render the output for on-line display, and in the case of OAAP, encoders proficient in multiple languages.

Metadata

Our metadata practices for translation documents were developed through a series of trials and internal discussions amongst catalogers, archivists, and scholars on the project. One challenge that presented itself early on was the need to be vigilant in the pursuit of consistency across a heterogeneous collection of document types. For logistical reasons, digitization of materials occurred in batches according to the type of document: monographs, manuscripts, broadsides, etc. With each new batch it became necessary to revisit solutions from the previous batch in order to ensure consistency in the handling of such details as dating conventions, the appearance order of author/recipient for correspondence and so on. Transcription and translation work of the actual contents of the text also raised questions regarding metadata and sometimes required refinements or outright changes to dates, authors or places as certain facts from the documents themselves became better known through research conducted by the OAAP project team[8]. In the final analysis, an in-depth metadata approach was adopted that provided data about both the original document and the translated work and included a joint review by both the translator and cataloger for the assignment of document titles.

OAAP translation documents inherit the metadata that was created to describe the original document, because both the translation and the original contain the same content and can be assigned the same metadata for subject analysis and name authority. Additional metadata was added that directly describes the translation work itself, such as the name of the translator, the language of translation, etc.[9]

| Metadata | Description |

| dc.contributor.translator | Proper name of the creator of the translated work |

| dc.date | Date of original work |

| dc.description.translation | Provides information about the translation: Name of translator, title of the source document, language of the translation and original document |

| dc.format | Translation [globally applied to all items] |

| dc.language | Language of translated document using the international standard IS0 639.2 "Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages"(e.g. : "spa") |

| dc.relation.isVersionOf | Provides link to original document [This "isVersionOf" qualifier corresponds to a matching "isReferencedBy" qualifier in the original] |

| dc.title | Translated title |

Table 1: Definitions for unique translation related metadata

Translations retain the date of the source document because we believe a researcher conducting a date-based search is more interested in the date of the document's actual contents than the date of its translation. The description (dc.description.translation) element provides a human readable reference to the source document, giving a clear explanation of what the translation work contains.

|

This document is an English translation of the "Carta de Angel Navarro al Jefe |

Figure 2: Example of a description for a translated document

Standardization of titles

The creation of translation titles proved to be less clear-cut than was first anticipated. While many of these could be handled with a simple default to common sense and tradition, others required a more flexible choreography to compromise between differing conventions based on language (dates written in the order month-day-year versus day-month-year, for example). Preliminary titles for translated works were based on archival finding aid information. In a number of cases, the finding aid used only English language titles regardless of the native language of the original text, so the original title in the native language had to be created as well.

The titles provided in the finding aids, while reliable for the most part, did reveal some interesting and unexpected infelicities. A good example of this was found in a 1597 Spanish manuscript. Deciphering the document was in itself extremely laborious, as there were signs of wear (holes, tears, etc.), the handwriting was exceptionally florid and extensive marginalia crowded the principal text from both sides of the page.

The content, or at least the parts that could be initially understood, seemed to indicate that this was a portion of the testament, or will, of one Diego Alvarez. However, after additional research during translation work, it was determined that this document, although legal in nature, was an appendix of sorts to the proper will, which was not owned by the Rice University library. The manuscripts dealer from whom these materials had been acquired, had failed to note that the "Testamento..." was only a portion, and tangential to, the document accurately reflected by the larger title. Therefore the actual translation of the document's content showed that this document was not the full will but rather a statement or "ordinance" related to Diego Alvarez' plan to make provisions for orphaned girls. The title was changed to reflect this:

Initial finding aid title: Testamento de Diego Alvarez

Revised native language title: Siguense las ordenancas de las donzellas huerfanas

Final translated title: The following are ordinances regarding the orphan maidens

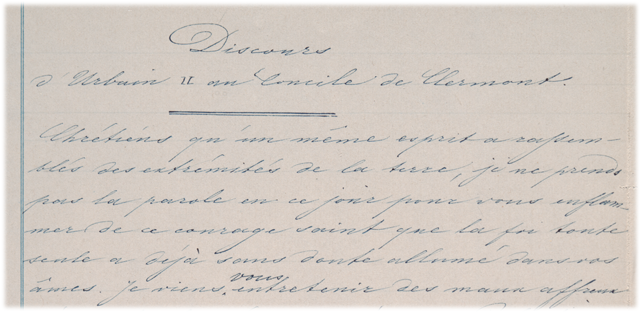

An example of how transcription work by researchers on the project provided information impacting native title formulation is an item from the "Charlotte & Maximilian" manuscript collection.[11] Initially thought to be a single large manuscript, it turned out to be a grouped document consisting of four separate texts written by the Empress Carlota when she was an adolescent. These consist of a brief fictional piece concerning refugees from the French Revolution who find themselves at the summer retreat of the British royal family, a speech written in the first person persona of Pope Urban II, calling on the Christian princes of Europe to go on crusade in the Holy Land, and two sermons to be delivered on Catholic feast days. Because of the differing interpretation as to what these texts represented (the creative endeavors of a devout and royalist teenager or simply homework?) a covering title was devised to include both such possibilities, namely "Recueil de petits exercices et d'œuvres créatives, sous la responsabilité de Carlota, l'Impératrice du Mexique" (Grouping of brief academic exercises and creative works in the handwriting of Empress Carlota of Mexico).

Figure 4: Selection from manuscript "Discours d'Urbain II au Concile de Clermont" written by the Empress Carlota, dated 1856

Another challenging aspect in metadata work for manuscripts and other unpublished printed texts was the construction of supplied titles. As a general rule, a supplied title is based on an initial quick reading of the item to be cataloged. Typically these sorts of works require qualifying segments of dates, places or people to help distinguish individual items, such as individual letters in a folder of similar letters. The convention we ultimately chose for assigning titles to correspondence was as follows: Letter From Author to Recipient/Date/Place Of Composition — with both date and place necessarily optional, depending on their actual appearance in the text.

Examples:

Carta de J.G. de los Santos a C. Antonio Vasquez, 23 de mayo 1830, Goliad

Lettre de Charlotte, l'imperatrice du Mexique, à son oncle, le duc de Nemours, le 11 fevrier 1856, Lacken

In a number of cases, the relevant dates and authors were not immediately apparent without a closer reading of the item's contents. This seemed to occur with some frequency in the notoriously difficult-to-read handwritten missives of Mexican civil servants and military men from the period immediately prior to the War of Independence in Texas. In other instances, a close reading revealed an additional author not previously noted. In some of the Spanish-language government documents the most prominent date on the piece might not in fact be the actual date of issuance or composition, and close reading was again required in order to sort this out.

Therefore, working closely with the translator of a text was a critical step in the formation of the final translation titles. After all translations were completed, a detailed review of translated titles was jointly conducted by the project translator, Lorena Gauthereau-Bryson (Americas Studies Researcher) and language specialist cataloger, Robert Estep, to ensure consistency with title formations across the collection. This standardization of titles included examining such things as:

- Consistency in the way dates and places are placed or formed within titles. Dates within Spanish language titles have different capitalization, punctuation and order than English language documents. Example:

Órden N. 1, Guatemala, 1 de agosto 1829

Order No. 1, Guatemala, August 1, 1829

- Consistencies in the way various title segments are displayed across similar document types (such as broadsides and letters). Example:

Initial title: El Presidente de la Republica a los Centro-Americanos

Revised native language title: Hoja suelta-Decreto, Guatemala, Guatemala, 9 de agosto 1825

Translated title: Broadside-Decree, Guatemala, Guatemala, August 9, 1825

- Consistency in the level of data used to create titles between the original title and translated title, for example, including subtitles in the translated title if subtitles existed for the original work.

- Methodology for creation of excerpt titles. The general rule is to supply a title for the excerpt, usually a chapter or section header plus the title of the larger work, placed within square brackets. Example: Savage America, Chapter I [Excerpt from: The Moral History of Women]

The OAAP collection is comprised of approximately 50 percent non-English texts, mostly Spanish with some Latin, French, and Portuguese. One of the key findings during this project was the importance of language skills in preparing metadata for multilingual collections. Having a working knowledge of the native language of the texts allows catalogers to better analyze contents to assign relevant subject terms and prepare descriptive titles.

Future of OAAP as a multilingual site

From the inception of the project, there has been a genuine desire to make the site truly hemispheric, reflecting the concept of the Americas as a community of nations with a shared, intertwined, and often conflict-ridden history. Since the documentary wealth of the Americas collection is multilingual (Spanish, English, Portuguese, and French, etc.), the in-house translation of selected documents is designed to expand the collection both in terms of quantity and accessibility, ideally forming a collection of originals alongside full translations in every language represented. One method suggested to achieve this goal is a formation of a community of students, scholars and researchers who could contribute full or partial translations to the archive. This long term effort could be part of a larger "journal" approach to the web site, where prominent scholars are invited to write editorials or host exhibits that foster a community focused on the field of hemispheric studies.

Another strategy for building OAAP to a full multilingual site is the addition of a multilingual user interface. Anecdotal feedback received to date has suggested that providing search mechanisms in a user's native language would be very beneficial, particularly so for researchers seeking non-English content. An even further extension of this ideal would be to take a step back and regard not merely the documents themselves or the user interface as targets for this treatment, but all aspects of communicative information related to the documents, such as translating the metadata used to describe the varying types of documents in the archive.

The translation of metadata may be as complex an undertaking as the translation of textual contents. For example, one of the advantages of Library of Congress (LC) subject headings has been their formulaic and yet flexible consistency, their overarching and sweeping categories combined with the richness of individual case-specific detail, each of these components reflective of disciplinary and historical certainty in their accuracy and validity. How then would one go about translating LC subject headings into Spanish, French, or Portuguese? For both Spanish and French the existence of databases of subject heading equivalents for LC subject headings has been a matter of library practice for some time, and with probably the same degree of universal usage and local tinkering as the LC subject headings in the English-speaking world. The Spanish version is Bilindex, and the French versions are RAMEAU (Répertoire d'autorité-matière encyclop�dique et alphab�tique unifié) for France, and Répertoire de vedettes-matiére for Canada. Portuguese subject headings are another matter, and although there are a variety of resources in both Brazil and Portugal, these tend to be discretely focused by discipline (medicine, law, sports, music, environment, etc.). However, a quick canter through any non-English language cataloging chat-room turns up a fair amount of wariness regarding adhering too closely to the perceived Anglo-centrism of the LC subject headings.

This wariness seems justified, as there appears to be a certain built-in bias in the creation of LC subject heading terms over time. LC subject headings, in regard to certain subjects (particularly history) are luxurious when treating English-speaking North America and Europe, and comparatively thin when treating Latin America or Africa. This relative paucity in regards to the southern portion of the continent was especially noticeable while cataloging materials for the OAAP. A few examples: the American Civil War receives more than 70 valid subject headings, one of which, "Campaigns", has a further breakdown of 219 individual battles; the American Revolution receives 40 subject headings, with a breakdown of 93 battles under "Campaigns", and the War of 1812 receives subject headings for 35 individual battles. In contrast, the 14-year war of Chilean independence has a list of three battles and the 10-year Mexican Revolution is provided with a list of eight battles. The overall chronological periodization of US history up to 1901 lists 33 broad time spans, in contrast to 13 for Mexico, eight for Chile, and a surprising three for Guatemala, which are, specifically, "History—To 1821", "History—1821-1945" and "Revolution, 1871". Thus, providing appropriate and accurate subject analyses and headings for the large numbers of items related to Guatemala's history in the early part of the 19th century required considerable creativity in formulating valid entries which reflected more detail than the bare bones of the historical possibilities as defined by LC. This raises questions regarding the value of perpetuating this bias by creating multilingual versions of existing LC subject headings. Perhaps efforts would be better spent exploring the use of alternative subject vocabularies produced in native languages either supplied directly by scholars or some other national lexicon.

Conclusion

The translations in the Our Americas Archive Partnership provide greater access to the contents of primary source materials of non-English languages. They support new research and emerging scholarship into inter-Americas and hemispheric studies. These resources also represent a corpus of materials that explore the digital treatment of "born-digital" translations including historical annotations, the semantic encoding of texts and methods for describing such materials in meaningful ways. These works and others can be explored at the OAAP beta site http://oaap.rice.edu/, and comments are welcomed.

Notes

[1] IMLS Award LG-05-07-0041-07.

[2] Read more online about these collections at http://oaap.rice.edu/collections.php.

[3]"IMLS grant abstract" found at http://oaap.rice.edu/about.php?page=documentation.

[4] Examples of historical abbreviations may be seen in the educational module, "Abreviaturas históricas" (Historical Spanish Abbreviations) http://cnx.org/content/m34696/latest/.

[5] For more information on the survey of existing online collections that appeared to contain "born-digital" translations, including a complete list of search sites and methodology, please see http://tinyurl.com/3qqhd48.

[6] http://www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/.

[7] Gorraez, José de and Escandón, José de. Guevara's Report to His Excellency, the Viceroy, regarding the Seno Mexicano missions made in the year 1756 [Excerpt from: Documents regarding the religious conversion in the Seno Mexicano and Sierra Gorda]. Translated by Gauthereau-Bryson, Lorena. Manuscripts. 1748. From Woodson Research Center, Rice University, Britton Collection of Early Texas and U.S. Civil War documents, 1597-1903, MS 009. http://hdl.handle.net/1911/36224.

[8] List of OAAP project team members can be found at http://oaap.rice.edu/about.php?page=project#people.

[9] A comprehensive list of translation metadata elements and input guidelines are available online [see "Application Profile - Translation Metadata" found at http://oaap.rice.edu/about.php?page=documentation.

[10] Alvarez, Diego and Cabello, Francizco. The following are ordinances regarding the orphan maidens. Translated by Gauthereau-Bryson, Lorena. Legal documents. 1597. From Woodson Research Center, Rice University, Britton Collection of Early Texas and U.S. Civil War documents, 1597-1903, MS 009. http://hdl.handle.net/1911/36220.

[11] This archival collection (covering the period 1846-1927) contains original letters from Charlotte of Belgium, chiefly as Carlota, Empress of Mexico as well as photographs, engravings, and drawings of Charlotte, of Mexico City, and of members of the Mexican military and other published materials regarding Maximilian's reign in Mexico. Only a small selection of Carlota's letters was digitized for this project. For more information on the complete collection, please see the archive finding aid at http://library.rice.edu/collections/WRC/finding-aids/manuscripts/0356/.

About the Authors

Lorena Gauthereau-Bryson is the Americas Studies Researcher for the 'Our Americas Archive Partnership', where her main focus is the translation and research of archival documents. She is fluent in English and Spanish and holds an MA in Hispanic Studies from Rice University and BAs in English and Political Science from Rice University. Her scholarly interests include US-Mexico border studies, Mexican-American literature, and hemispheric studies.

Robert Estep is a Senior Copy Cataloger at Fondren Library, Rice University, with over 20 years experience. He received a BA in English (minor in French) from The University of Texas at Austin. Robert is fluent in multiple languages. Besides providing subject-area metadata for the Our Americas Archive Partnership he assisted in the proofreading and transcription of some Spanish-to-English and French-to-English translations, and translated some items from Portuguese.

Monica Rivero is the Digital Curation Coordinator for the Center for Digital Scholarship at Rice University. She worked as the project manager for the 'Our Americas Archive Partnership'. She holds an MLIS from University of North Texas Graduate School of Library and Information Sciences and a BA in Business management from Sam Houston State University. Monica has over 10 years experience in project management in the private sector.

|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |