|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |

D-Lib Magazine

March/April 2010

Volume 16, Number 3/4

Using Omeka to Build Digital Collections: The METRO Case Study

|

Jason Kucsma |

Kevin Reiss |

Angela Sidman |

doi:10.1045/march2010-kucsma

Abstract

Abstract

In September 2008, the Metropolitan New York Library Council (METRO) began work building a directory of digital collections created and maintained by libraries in the metropolitan New York City area. METRO built the directory using Omeka, an open source collection management system, as a test to determine the viability of this platform for member libraries interested in using Omeka to build and deliver their own collections. This paper addresses Omeka's strengths and weaknesses as a software platform for creating and managing digital collections on the web. The analysis includes an examination of original record creation and the extensibility of the system through the use of plug-ins.

Project Background

The digitalMETRO project was born from the Metropolitan New York Library Council's (METRO) 2007-2010 Digital Library Services Plan. The plan serves as a guiding document for METRO's work in helping member libraries build and maintain unique digital collections and provide access to them online. Since 2005, METRO has provided over $300,000 in digitization grants to fund over 30 digitization projects. METRO also provides a diverse curriculum of workshops focusing on digital conversion, metadata for digital collections, digital collection management software, and related areas of emerging technologies for libraries. In addition to ensuring these programs continue to provide training and resources to member libraries, the Digital Library Services Plan also recommended the creation of a directory of digital collections in the METRO membership to increase discoverability and access to digital collections.

With the charge of creating a directory of digital collections, Jason Kucsma, METRO's Emerging Technologies Manager, served as Project Manager and assembled a small project team to begin working on the directory. Angela Sidman and Kevin Reiss, librarians at a METRO member institution, joined the project as the Metadata Librarian and Web Developer in October 2008.

Choosing Omeka

One of the first decisions we had to make was which collection management system we would use to build and deliver the directory on the web. With our goals of highlighting member library collections and of testing software which could be used for future collection building, we evaluated three possibilities, CONTENTdm, WordPress, and Omeka. Each of these systems was judged against our expectations for digital collection management systems:

- Attractive, easily customizable visual design (themes)

- Ease of installation

- Extensible design approach which enables the alteration of existing and the addition of new functionality

- Flexible approach to metadata

- Support for web standards (CSS, XHTML, RSS)

- Import and export functionality which utilizes standardized data formats (CSV, XML, JSON)

METRO licenses a hosted CONTENTdm (CDM) instance from OCLC and two of the project staff had worked extensively with the product when building the metadata for the METRO-funded Digital Murray Hill Project. While CDM is a system that supports collections with robust metadata and that contain a wide array of digital formats it lacks some characteristics that are desirable in a modern digital exhibition tool. The out-of-the-box CDM user interface makes it difficult to browse collections by subject and set, and CDM does not support any of the interactive features that many users expect in a web interface such as tagging, the easy sharing of content via social networking tools, and a mechanism to accept end-user feedback on the web. CDM does provide a basic Application Programming Interface (API) that allows for some modification of default CDM behavior, however we felt that this API was an inadequate tool for building the types of features we wanted to include in the digitalMETRO website.

The second system under consideration was WordPress, an open-source content management system which project librarians had utilized to create a separate user interface for Digital Murray Hill after authoring the metadata in CDM. WordPress has well-documented theme mechanisms for customizing the display of content, and an expanding pool of plug-ins that can be used to modify content behavior. Unfortunately, WordPress does not have a well-developed mechanism for supporting the types of collection-building workflows and metadata-creation common to archives and libraries, such as a tool for batch importing tab-delimited or comma separated value (CSV) files. Creating a plug-in to support these activities was beyond the modest scope of this project.

Our interest in deploying a feature-rich digital exhibition tool next led us to consider Omeka, a relatively new open source collection management system that was created by the Center for History and New Media (CHNM) at George Mason University. Omeka's developers appear to have taken design inspiration from WordPress's success as a general purpose open-source content management system. Wordpress is widely known for its ease of installation and high-level of functionality. In this vein, Omeka developers have touted their platform as a "next generation web publishing platform for museums, historical societies, scholars, enthusiasts, and educators." Our project team thought libraries might also fit into that family; particularly smaller libraries with limited technical staff or financial resources to build and deliver digital collections online. The simplicity of installing and configuring the Omeka system rivals WordPress's ease-of-use, leading CHNM Director Dan Cohen to suggest Omeka is "Wordpress for your exhibitions and collections." Omeka also utilizes the same theme and plug-in mechanisms as Wordpress to provide its users with a means of customizing and creating new system behavior.

Another feature which project staff found attractive was Omeka's strong and flexible approach to metadata representation. Libraries can work with either the default Dublin Core set, import other metadata sets of their choosing, or create their own customized metadata vocabulary. Additionally, according to the CHNM website: "Omeka provides cultural institutions and individuals with easy-to-use software for publishing collections and creating attractive, standards-based, interoperable online exhibits. Free and open-source, Omeka is designed to satisfy the needs of institutions that lack technical staffs and large budgets." This fell in with METRO's goal of exploring new systems as vehicles for collection building and exhibitions that could be recommended to METRO members and other small and medium libraries and archives. Our exploration of potential digital collection management systems overlapped with the Fall 2008 release of the 0.10 beta version of Omeka and the digitalMETRO team decided to join the growing number of projects using the system in beta.

Project Scope and Specifications

The digital collections directory project (digitalMETRO) that we executed using Omeka began with a survey of digital collections in the METRO membership that continued as the project took shape. Kucsma built an initial list of discrete digital collections created and maintained by METRO member libraries. We established a collection policy rooted in the desire to represent as many collections as possible given our limited personnel and time. A collection would be included in the digitalMETRO directory if:

- the creating institution was a member of the Metropolitan New York Library Council

- the institution owned these resources and has permission for them to be accessed freely online

- the collection included at least 30 resources (images, audio files, finding aids, etc...)

The last criteria was established to exclude small exhibitions that featured only a handful of digitized resources. To facilitate user-submitted collections that could be added to the directory once the project was made available online we anticipated taking advantage of Omeka's "Contribute" plug-in. This added feature would allow libraries to submit collections to the directory that might not have been included in the first phase of surveying. Additionally, we also created a simple spreadsheet template that libraries could use in the future to submit multiple collections for inclusion in the directory using Omeka's CSV Import plug-in which will be discussed later.

Setting up Omeka

Omeka is a conventional Linux Apache Mysql PHP (LAMP) application. Running Omeka for a production website on Windows or a Macintosh is not recommended at this time. Omeka also utilizes the open-source image processing package, ImageMagick, to enable the auto resizing of images added to the system for display. A basic familiarity with Apache web server and Mysql database server administration is required for a successful installation. For a user comfortable with setting up LAMP applications, an Omeka installation can be efficiently accomplished in a very short amount of time. For novice web developers installation may be more challenging. Omeka has an active and growing online community where help for installation problems can be sought through the web forums available on omeka.org or the Omeka developer's Google group.

The digitalMETRO Omeka instance is hosted commercially by Bluehost an Apache 2 Web Server running on Linux. Omeka is built using the Zend Framework a robust, open-source PHP web application programming framework. Zend is a Model View Controller (MVC) programming framework the use of which enabled Omeka to be designed for extensibility out-of-the-box. Omeka has two primary means for extension: the theme, which controls the application's visual presentation, and the plug-in, which is used to expand and alter the functionality that the base Omeka application provides.

We selected "Winter," one of the eleven existing available Omeka themes, as the basis for our display. Themes can be downloaded from the themes section of the Omeka site. Our modifications included some minor changes to the text size and color scheme as well as the addition of a custom header created from royalty-free vector art licensed from iStockphoto. To add further functionality, we utilized the following standard plug-ins http://omeka.org/add-ons/plug-ins/ within our Omeka instance:

| Adam Output | Adds the Atom Syndication Format to the list of available output formats. |

| COinS | Adds COinS metadata to various item pages, making them Zotero readable. |

| Contribution | Makes an Omeka site into one that accepts public contributions. |

| CSV Import | Imports items, tags, and files from CSV files. |

| Dropbox | Allows Omeka users to 'batch upload' a large quantity of files at one time. |

| Exhibit Builder | Builds rich exhibits using Omeka. |

| Google Analytics | Adds Google Analytics' tracking code to an Omeka Instance. |

| HTML Purifier | Protects Omeka web forms from XSS by filtering HTML/XHTML using the HTML Purifier library. |

| Lightbox2 | Adds functions for themes to add image overlay functionality to Omeka themes using Lokesh Dhakar's Lightbox2 Javascript library. |

| OAI-PMH Repository | Exposes Omeka items as an OAI-PMH repository. |

| Simple Contact Form | Adds a simple form through which users may contact the administrator. |

| Simple Pages | Allows administrators to create simple web pages for their public site. |

| Social Bookmarking | Inserts a customizable list of social bookmarking sites below each item in the Omeka database. |

| Sort Browse Results | Allows sorting of results on browse items page. |

Plug-in deployment is straightforward. Once the source code for a plug-in is moved to the appropriate directory in an Omeka installation a site administrator need only use the administrative interface's plug-in management section to install and configure the available options for the plug-in. Plug-in development is happening at a rapid rate with a growing community of developers actively contributing new plug-ins and improving the existing ones.. In fact at the time we were compiling this report, a new Social Bookmarking plug-in became available and we added it to digitalMETRO in less than five minutes. There are a number of additional Omeka plug-ins that will be of particular interest to libraries, archives, and museums including the OAI-PMH Harvester (OAI Harvesting Support) and the Geolocation plug-in (adds location information and maps to Omeka).

The Omeka theme and user experience

Omeka users can easily customize the display and behavior of their websites by selecting one of a number of pre-packaged Omeka themes and by manipulating the well-designed CSS that controls the theme's basic look and feel. Looking at the existing digitalMETRO site for illustrative purposes, we can explore some of the more useful standard Omeka features.

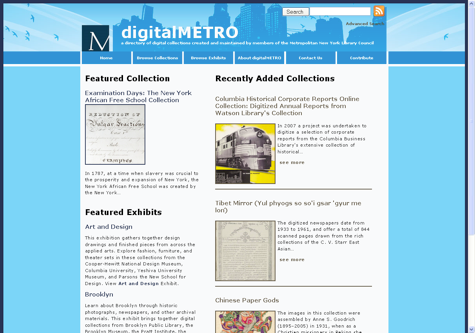

Figure 1

The screenshot in Figure 1 above displays the main page of our Omeka instance. Visitors to the site are given a number of options which they can use to begin exploring the site. Casual browsers may be drawn to the "Featured Collection," which is randomly generated by Omeka each time the home page is refreshed. Site administrators can determine which items will be included in this rotating cast simply by checking a box in the item record. The site can also be set to feature "Recently Added" items to a collection, and the number of items displayed can be set according to a specific collection's needs. Users may do a simple search using the search box in the top right corner of the page or they can conduct an advanced search using the link just below the simple search box. While the current search tools offer adequate, if limited, access to the collection, Omeka 1.2 promises to feature a more robust search tool implemented through a plug-in that will use the well-known open source search engine Lucene, which has an existing Zend framework interface.

A series of tabs affords the user several additional options for navigating the site. In addition to the expected administrative tabs that direct people back to the home page or to the «about» page to learn about the site, the Browse tab is perhaps the most useful. This directs users to a page where they can browse the directory via ordered lists of tags, collection creators, or dates that collections were added to the directory.

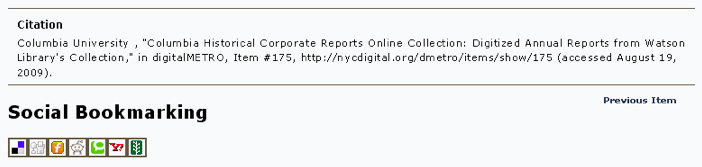

Sharing resources from an Omeka collection is easy as well. Omeka generates both RSS and Atom feeds to support syndication of item content (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The clean and simple URLs generated for items in Omeka make it easy for users to share an item from the system via email or other social networking tools. This stands in direct contrast to most proprietary digital content management systems such as CONTENTdm or Ex Libris's Digitool which typically generate lengthy URLs that are hard to share and dificult for many email and social networking tools to parse. Depending on the browser being used, additional sharing options will be featured in the URL window as well. Omeka has a COinS (Context Object in Spans) plug-in that embeds bibliographic metadata in the HTML of an Omeka Item page, making the site compatible with bibliographic research tools like Zotero. Additionally, a Social Bookmarking plug-in allows users to share a given resource on any number of social bookmarking sites like Delicious, Facebook, Digg, Yahoo!, Technorati, and more (See Figure 3 below). The Omeka theme has a documented API that makes it easy for web administrators to deploy and customize these types of features to provide the type of experience most users expect on today's web.

Figure 3

Metadata Management with Omeka

Throughout the project we made extensive use of one of the richest and most fully realized aspects of Omeka: its metadata support. By default, Omeka supports the standard Dublin Core metadata set. Omeka also makes it easy to develop and implement project-specific metadata sets as needed and have them easily feed into the Omeka display and editing infrastructure. There are two ways to do this:

- Through the creation of Custom Omeka Item Types (http://omeka.org/codex/Managing_Item_Types)

- Though the creation of new Element Sets (http://omeka.org/codex/Creating_an_Element_Set)

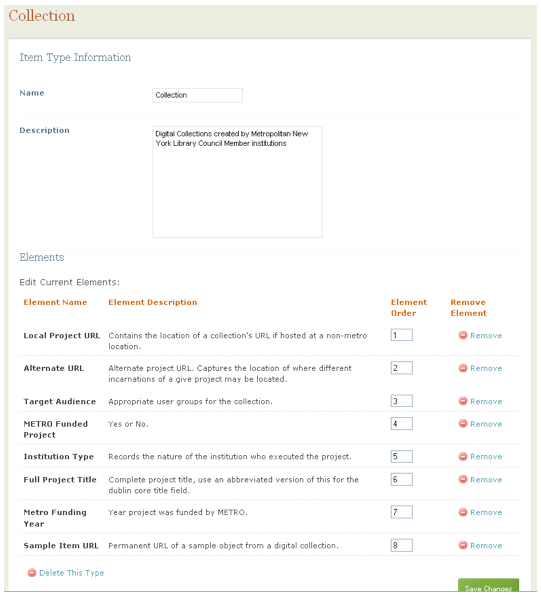

These two options mean Omeka can support the creation of a locally defined metadata set or easily add support for an existing metadata standard. An example of this is the inclusion in the Omeka 1.0 release of a plug-in that makes the Extended Dublin Core Metadata Set available as a metadata or element set choice for any Omeka project. A plug-in could be created for any metadata set desired by an Omeka user. This extensible metadata architecture ensures that Omeka will work well with future metadata initiatives since they can be easily supported using either one of these mechanisms. Both Custom Item Types and Element Sets are easily displayed and manipulated in both the Omeka public end-user display theme and from within the back-end Omeka administrative environment (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Building digitalMETRO with Omeka

Media and content

Omeka supports fourteen different item types in its standard installation. These run the gamut from traditional print resources such as still images and text to moving images, oral histories, and email messages. Within each of these item types Omeka allows for multiple file formats, including the common digital collection components JPEGS, PDFs, and TIFFS. In order to deal with our unique purpose of building a digital collections directory with digitalMETRO, staff needed a new item type, "Collection", which did not exist in the standard installation. To address this issue we used Omeka's customizable infrastructure to build our own unique <<Collection>> Item Type and added the the following project-specific elements to each record:

- Local Project URL

- Alternate URL

- METRO Funded Project (whether or not this project was funded by a METRO digitization grant)

- METRO Funding Year (if applicable)

- Institution Type (academic, public, or special library)

- Full Project Title

- Sample Item URL (for representative images from a given collection)

Authoring individual records

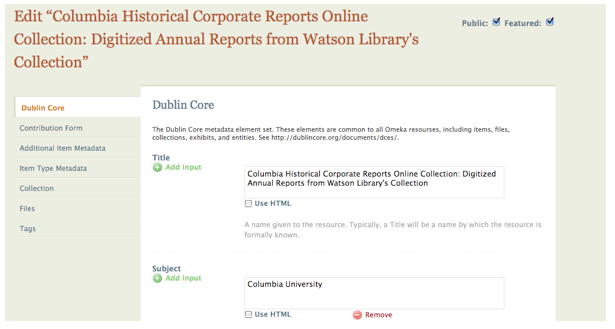

Creating and adding item content within Omeka occurs primarily in the web browser via the password-protected administrative interface. Like the public-facing side of the Omeka instance, the admin interface is implemented using a theme architecture that can be customized to meet the needs of a particular Omeka project. Individual records, or items in Omeka's nomenclature, may be authored in the administrative interface by filling out a tabbed customizable metadata template (see fig. 5).

Figure 5

There is a "files" tab where media associated with a given item can be uploaded and associated with a given record. The Metadata Librarian entered individual records directly into the administrative interface using the template. This template is divided into six tabs which reflect the intellectual organization of the project's metadata:

- Dublin Core: Basic Dublin Core Metadata Element Set common to all Omeka projects

- Contribution Form: Contains data elements pulled from the Contribution plug-in used by member libraries

- Additional Item Metadata: Custom metadata fields added by project staff to augment the standard DC data elements

- Collection: Project-specific metadata associated with the custom item type "Collection"

- File: Associates digital image files with metadata records for display purposes

- Tags: Allows for the addition of uncontrolled or loosely controlled vocabulary to aid in subject analysis and collection description

The bulk of the Metadata Librarian's work occurred in the Dublin Core (DC) tab of the item creation form. It was here that project description (Title, Creator, Format, Description) and subject analysis (Subject) took place. For librarians with experience in creating records using DC the item creation template is familiar and intuitive. For librarians accustomed to creating records using the rigid structure and numeric field tags of MARC, the Omeka interface offers a soft entry into new types of metadata creation. The web form provides a blank field for each data element and users may build from there, adding fields through a simple click on a "plus" button labeled "Add input." Under each data element is a definition of the element's purpose and examples of proper usage. These data element definitions would be particularly useful for projects in which there are multiple record creators, including students or interns, and for librarians with limited experience in creating non-MARC metadata.

While it was easy to begin authoring records in the administrative interface, the limitations of the system became clear as we started working with a greater volume of records. For example, there is no templating system or other mechanism for populating related records with common data within the administrative interface. To ensure consistency between records, the user must rely on time-consuming tactics such as copying and pasting from previously created records or from source sites like the Library of Congress authority files. Additionally, navigating within a single record was time-consuming, as the template's layout required a burdensome amount of scrolling. This scrolling could not be avoided as the "Save Changes" button appeared only at the bottom of the screen and regular saving was key to successfully authoring records in Omeka. The item creation template was, of course, web based and if a user accidentally navigated away from the active record, either to another tab within Omeka or to a site from which data had to be copied and pasted into the form, then any unsaved content within the record disappeared. The system does not offer a preventative warning asking if the user would like to save any unsaved changes before closing the record. On several occasions we lost time and detailed intellectual work by accidentally navigating away from the item creation form.

These issues make Omeka problematic as a serious choice for a project that will involve large-scale or detailed metadata creation, since using it in the fashion digitalMETRO attempted revealed serious data consistency issues. However, considering the extensible MVC architecture on which Omeka is built, all of these issues seem fixable if the development community would take notice. As better documentation of the Omeka administrative theme and Omeka plug-in API develop, these issues could be addressed. For example, support for controlled vocabularies could come via a plug-in that could make a selected vocabulary available for guided editing in the metadata authoring interface. A more streamlined editing interface that supports both record templates and data-typing of metadata fields could be accomplished through rewriting some of the MVC code within the administrative theme.Importing records into Omeka

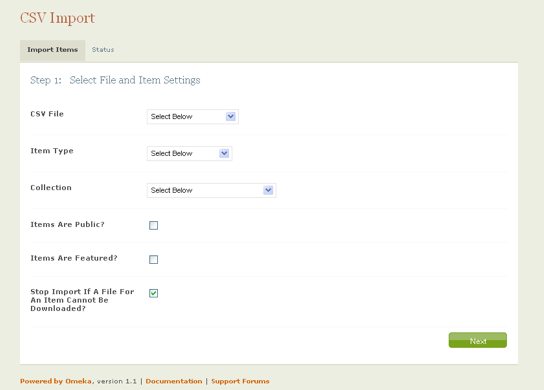

Larger groups of records and their associated media may be batch loaded from CSV files beginning with the Omeka 1.0 release. The <<CSV-Import>> plug-in allows site administrators to easily import and map metadata into the available metadata elements and Item Types in an Omeka installation. DigitalMetro project staff quickly moved to batch loading records through the CSV Importer as a means of bypassing as many of the administrative interface's shortcomings as possible. The project manager created an Excel spreadsheet and populated it with key data elements which could be determined through a preliminary viewing of a potential site: Creator, Title, URL, METRO funding status, etc. The Metadata Librarian then reviewed the spreadsheet and ensured that the completed fields complied with controlled vocabularies before the web developer loaded the file into Omeka.

To expedite record creation in digitalMETRO finalized CSV spreadsheets were loaded to plug-in's import directory (using the CSV Importer plug-in).

Figure 6

After this, librarians used the plug-in's import wizard to map their records, metadata, and media into the system. Using the wizard the Item Type of imported records was defined and each of the spreadsheet's columns was assigned to the appropriate metadata element. The import wizard is also able to import tags, and media associated with a given record.

This process created a queue of skeleton records which the Metadata Librarian could then enhance through description of subjects, formats, additional authors, and other data before making the records viewable on the public side of the site. The benefits of moving to batch loaded CSV files were immediately clear. The use of spreadsheets allowed the Metadata Librarian to easily populate fields with shared data, which improved consistency within and between records and also decreased the time spent on cutting, pasting, and scrolling. This, in turn, led to a decrease in the number of records lost by bringing metadata and associated images in together at the same time.

Intellectual Control and Tagging within Omeka

Even with batch loads, control over data within Omeka is loose. Catalogers more comfortable with the tight intellectual control offered by a traditional library information system or a digital content management system like CDM may be disappointed by the weak search and retrieval features and the inability to carry out basic find/replace tasks or other global changes within the item-creation module. The weakness of the intellectual control provided by Omeka means that for a project of any size or scope it is crucial for librarians to get their records right the first time around, when they author them. This is not necessarily easy, as Omeka does not support controlled vocabularies such as LCSH, AAT, or the Thesaurus of Geographic Names. Metadata authors must work around the system to ensure that they enter correct, consistent, and authoritative data into their records. For this project multiple strategies were employed to control headings, including cutting and pasting directly from authority files, loading standardized data through batch loads, cross-checking through keyword searches on the public site, and exporting alphabetical lists of subject headings and tags into tab delimited files for review by hand. In addition to the difficulties faced in creating consistent data content, there was an additional hurdle in that Omeka does not include a record validation function to make sure that core fields are populated.

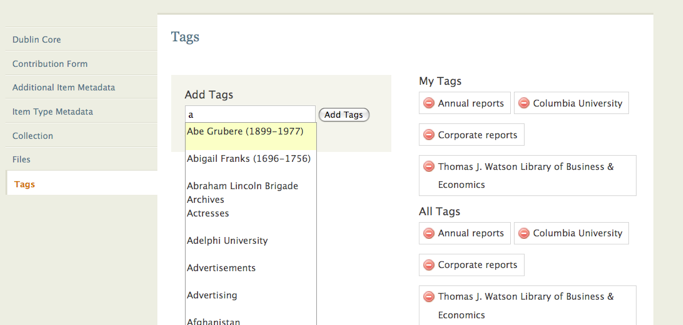

The tagging mechanism built into the item creation module offers a bright contrast to the difficulties of working with controlled data (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Our project staff opted to take full advantage of the tags, building them into a robust companion to the more structured DC data. The same core metadata fields found in the item records are repeated in the tagging, only this time instead of relying on controlled vocabularies, natural language terms are used. Compare, for example, the structured and unstructured terms used to describe John Jay College's collection "Crime in New York 1850-1950," http://nycdigital.org/dmetro/items/show/18.

| Controlled vocabularies | Tags | |

| Creator | John Jay College of Criminal Justice | John Jay College |

| Additional creators | Turkus, Burton B. | Burton B. Turkus |

| Lawes, Lewis Edward, 1883-1947 | Lewis Edward Lawes (1883-1947) | |

| Subjects | Homicide | Homicide |

| Organized crime | Organized crime | |

| Criminal investigation | Criminals | |

| Sing Sing Prison | Sing Sing Prison | |

| Death row inmates | Inmates | |

| Materials | Forensic photographs | Crime scene photographs |

| Identification photographs | Mug shots | |

| Transcripts | Trial transcripts |

A keyword search on the public site will pull up content added through controlled vocabularies as well as the tags. In the absence of traditional see/see also references, which are built into library catalogs and databases, the hope is that this combination of structured and unstructured data will help lead non-expert users to the information they seek. Even an experienced librarian might not immediately think to search for "Identification photographs" but the more commonly used "Mug shots" will guide users to the same authoritative data and with a deal less frustration or confusion.

Plug-In Modification

In order to add desired functionality that did not exist for digitalMETRO we used Omeka's plug-in architecture. Our plug-in work falls into two categories. First, we modified the existing code of several plug-ins. Secondly, we engaged in some new plug-in development that will attempt to increase the findabilty of digital objects within Omeka collections.

We first made minor updates to the Lightbox2 plug-in that had been written for Omeka .10 to run properly on Omeka 1.0. We also modified the Contribution plug-in so that libraries could submit recommendations of collections for inclusion in digitalMETRO. As written, the contribution plug-in was not particularly suited to our project design since it was built to facilitate self-archiving by object authors. For digitalMETRO, we configured the form to solicit some basic metadata about collections that visitors would like to see added to the directory. Once the form is submitted, a skeleton "non-public" digitalMETRO Collection Custom Item Type record is created and queued for the Metadata Librarian to complete and make public on the site. While our project sought to gather information on digital collections it is easy to see how a feature like this can allow cultural heritage institutions to quickly and easily create sites to collect information and resources from individuals around a certain topic or event. For example, The April 16 Archive site,which is dedicated to collecting and preserving stories about the Virginia Tech tragedy, uses the contribute feature to solicit stories, pictures, and audio files related to the campus shooting.

Modifications to existing Omeka plug-ins are relatively easily achieved since Omeka has been implemented as an MVC application, so each plug-in conforms to a convention familiar to most web developers. Plug-ins are composed of a directory structure that mirrors a standard MVC convention with a "view", "controller", and for more complicated plug-ins a "model" directory. The modifications of the contribution plug-in mostly happened at the view level, though the internal data structure that stores information about contributions needed to be adjusted to be capture the data from submitters that we wanted. The "controller" file also needed to be modified in order to map contributions directly to the custom "Collection" Omeka item type we used to code each digital project description.

New Plug-in Development

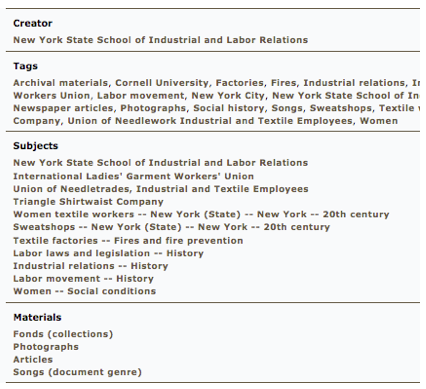

In order to advance the project's goals of highlighting the collections within digitalMETRO we are developing two plug-ins, a XML Sitemap generator and an Category Browser that turns any Omeka metadata element into a browsable category. The first will enhance the site's discoverability by exposing the public content of an Omeka instance content in the XML format defined by the sitemaps protocol http://www.sitemaps.org/. This file can then be submitted formally to search engines like Google or Yahoo! to ehance these tools crawling of the site.

The second plug-in enables an Omeka instance to be easily browsed by individual metadata elements and the values assigned to them. This is not currently an option within a standard Omeka installation. These elements are termed «categories» in the navigation options that appear within an Omeka theme when the plug-in is enabled. The plug-in seeks to ensure the each of the category browsing options is represented with a clean URL, that can be used effectively by search engines and end-users alike. digitalMETRO currently has browsing enabled by the Creator, Format, Subject, and Type elements.

The plug-in also provides an administrative screen that enables the site administrator to select which specific elements will be the category browsing choices in the public theme. This plug-in substantially increase the number of different access points users have to items in an Omeka collection since it also converts the the individual item display of selected choices into active browsing links (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

The selected browsing"categories" and the individual values assigned to each of them are also included in the sitemap generated by our sitemap plug-in. We are planning to submit both of these plug-ins for review by the Omeka development team and plan to release them for general use by the Omeka community if the are judged worthy of inclusion in the public list of plug-ins listed on the Omeka project site.

Given our assertion that Omeka's extensible design and the emerging and expanding set of plug-ins that enhance the software's functionality make it an exciting and potentially empowering tool for cultural institutions who have web development skills on staff, the existing Omeka project developer documentation has the potential to be a limitation to theme and plug-in development at the moment. The project documentation has lagged quite a bit behind the actual development that has occurred in the fifteen months we have been working with the system. This will need to be improved upon if Omeka is going to fully serve the needs of the audiences drawn to its flexible infrastructure and low barriers to implementation. There is an active developers' list and help forums on the Omeka site, but the Omeka Codex (http://omeka.org/codex/Documentation) needs to improve to the level where a competent library Web Manager or Web Librarian can start working with themes and plug-ins using more clearly defined examples to get started. At the moment, detailed customization work requires combing through source code to find a suitable example or a full explanation of a given function's parameters. This stands in contrast to the much larger pool of documentation and examples available for more widely used open source systems like WordPress.

Experiments in Exhibition Building

Omeka was developed with the express needs of museums, historians, and educators in mind. The software's origins in the arena of cultural institutions could account for what is, by library standards, weak intellectual control within the admin site. However, its development at George Mason's Center for Social History and New Media also directly led to one of Omeka's greatest strengths: exhibition building. Once users have created records within the system they can, with great ease, put together exhibits which shine a brighter light on related groups of material. A site editor fills out a web form to determine top level data such as Title, Slug, and Theme, then assigns section metadata, and finally adds individual records to the section. A given exhibition may have multiple sections, thus allowing for more complex relationships between digital objects. Templates make the layout of individual records semi-customizable within exhibits. Some templates give precedence to images while others allow for a greater expanse of exhibition-specific didactic text.

Exhibition-building fell on the margins of METRO's project goals and digitalMETRO does not fully exploit this feature's true potential. Nevertheless, project staff did create two exhibits which appear on the lower left side of the homepage as "Featured Exhibits." The "Art and Design" collection offers a good example of how the exhibition feature can be used for educational or curatorial purposes. This exhibit gathers together design drawings and finished pieces from across the applied arts. Site visitors may explore fashion, furniture, and theater sets through multiple librarys' collections, including the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, Columbia University, Yeshiva University Museum, and Parsons the New School for Design. In this case, the exhibition was built around the unifying theme of design history and illustrated the range of materials owned by METRO's member libraries. The strength of the exhibition feature is in its ability to convey a curatorial perspective in a dynamic, interactive setting which guides users from object to object while providing expert contextual information alongside standardized metadata and social tagging.

Conclusions

Omeka has great potential to effectively and efficiently support small and medium-sized digital collection building and online exhibitions for libraries and archives. The software is well-suited to enable librarians, archivists, and curators to work effectively in the context of their disciplines. The core Omeka software architecture and design are well-suited to allow the software to expand and improve as the user community grows. It is also well-positioned to serve as a tool institutions can use to repackage existing digital collections in a new, modern web exhibition framework with the availability of a robust CSV import option that can bring both metadata and media into the system.

Continued improvement of the Omeka administrative interface within this architecture will help it become a more viable digital collection building solution for libraries and archives. We experienced a good deal of frustration navigating through the interface to create records. We also had serious concerns about the ability to create consistent and detailed metadata within the administrative interface. The ability to create and manipulate metadata in a spreadsheet and populate skeleton records in Omeka works around some of the administrative interface issues, but there is still room for improvement in how a user creates records online. Omeka's search and retrieval capabilities also need to improve for it to become a more fully realized digital collection management tool. At this writing the Omeka development is working to utilize the Apache Lucene support with the Zend framework to provide a more effective full-text search interface for Omeka. It is hoped this effort will result in a new "Lucene" plug-in for the Omeka 1.1 release.

Despite these limitations Omeka is very well-positioned within its target market of small to medium-sized institutions that need an easy-to-deploy, effective, professional tool to make digital library, archival, and museum content available on the web. It is important to measure Omeka's functionality, features, and limitations against some of the same functionality, features, and limitations of a proprietary system. We hope that our experience will help other institutions evaluate Omeka as a possible collection management system for their digitization projects and anticipate and overcome any of the obstacles we encountered.

References

006_digsurveyreport.pdf. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://www.metro.org/images/stories/pdfs/2006_digsurveyreport.pdf.

2007_digplan.pdf. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://www.metro.org/images/stories/pdfs/2007_digplan.pdf.

Cohen, D. (2008, February 20). Introducing Omeka. Dan Cohen's Digital Humanities Blog. Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://www.dancohen.org/2008/02/20/introducing-omeka/.

Dave Lester's Finding America >> New Omeka Release 0.10 Beta. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://blog.davelester.org/2008/11/12/new-omeka-release-010-beta/.

digitalMETRO. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://nycdigital.org/dmetro/.

Explore Murray Hill through Images and Maps << Digital Murray Hill. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://murrayhill.gc.cuny.edu/.

Model-view-controller — Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Model%E2%80%93view%E2%80%93controller.

Omeka | Documentation - Omeka How To. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://omeka.org/codex/Documentation.

Omeka | Home. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://omeka.org/.

OpenURL ContextObject in SPAN (COinS). (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://ocoins.info/.

The April 16 Archive. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 23, 2009, from http://april16archive.org/.

WordPress > Blog Tool and Publishing Platform. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://wordpress.org/.

Zend Framework. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://framework.zend.com/.

About the Authors

|

Jason Kucsma is the Emerging Technologies Manager at the Metropolitan New York Library Council where he manages METRO's Digitization Grant Program and is the point person for member inquiries related to the resources, training and referral services associated with digitization, digital preservation and emerging technologies issues. He is a recent graduate of ALA's 2009 Emerging Leaders Program and is an adjunct instructor in Rutgers's Library and Information Science graduate program. |

|

Kevin Reiss is a University Systems Librarian within the City University of New York's Office of Library Services. Kevin's primary areas of professional interest are library web services, information retrieval, building digital collections, and information processing standards. Kevin holds a Master's degree in Library and Information Science from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. |

|

Angela Sidman is the Electronic Resources Systems Librarian in the City University of New York's (CUNY) Office of Library Services (OLS). Since joining OLS in 2009, Angela has provided system-wide support for the acquisition, licensing, and maintenance of CUNY's cooperative electronic resources. Angela graduated with a Master's degree in Information Science from the University of Michigan and a Master's in Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies from the University of Edinburgh. |

|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |